Ty Burr of the Boston Globe has described the film ‘Hunger’ as a “look at hell and the hunger for freedom”. The film was reviewed on March 27th. Here is the review in full.

‘Hunger’ brings us into its central narrative slowly, circling it like a bird afraid to land. This is the Bobby Sands’ story, true, but we don’t even see Sands until well into the movie.

First, we follow a sad-faced prison guard (Stuart Graham) from his Belfast home (he checks under his car for bombs) to his job “interrogating” inmates at The Maze. Then we live with two imprisoned Irish Republican Army members, Davey Gillen (Brian Milligan) and Gerry Campbell (Liam McMahon), in their cell for a while, watching them smuggle tiny messages to headquarters and paint the walls with their own excrement.

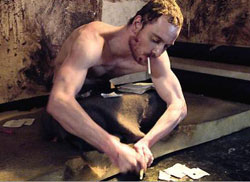

About 30 minutes in, those walls are pressure-hosed clean, the film’s ground shifts, and we meet Sands (Michael Fassbender), the Provisional IRA leader who gained international headlines when he starved himself to death over a two-month period in 1981. As Fassbender plays him, Sands is alarmingly thin to begin with, but he’s strapping, too – all muscle and implacable political purpose.

Margaret Thatcher’s England has rescinded the IRA prisoners’ Special Category Status, treating them as common criminals. Furious, they refuse to wear prison clothes, shave, or use the toilets. Sands’ hunger strike just ups the pressure and takes it public.

Not that we hear about the world’s response. ‘Hunger’ is directed by the British artist Steve McQueen, and it’s the first of his films not designed as an installation for a museum or public space. It looks like a ‘real’ movie – there are actors and a story line, dialogue and sets – but it doesn’t follow the standard rules of engagement for commercial narrative cinema.

It’s not a Bobby Sands biopic, for one thing, not with all those other characters, nor is it a pro- or anti-IRA political screed. The movie defiantly, even perversely, refuses to pull back for a wider frame of reference, aside from Thatcher’s unyielding voice on the radio. (It’s as if she’s the country’s head warden.) Once we’re in the Maze, we never leave.

So what is ‘Hunger’? Unexpectedly, a visually ravishing tour of hell and a meditation on freedom that at best is wordlessly profound and at worst interestingly obscure. McQueen seems to be aiming for the magisterial grace of Robert Bresson’s great 1956 prison movie ‘A Man Escaped’, but if he doesn’t come close, he has still made a work of electrifying images that cohere into a larger sense. The subject is the dangerous, necessary human hunger to break one’s bonds: Northern Ireland from Britain, the prisoners from their cells, Bobby from life. McQueen just tells his tale on the micro level. He’s more fascinated by a fly on the cell wall than the machinations of politicians.

The centerpiece scene of ‘Hunger’ is a 17-minute single shot of a conversation between Sands and a profane, clear-eyed priest (Liam Cunningham) as they argue over the ethics of starving oneself to death. It’s an audacious and absurdly compelling sequence, written and played within an inch of its meaning, but McQueen’s camera just hangs back and watches it build. “I want to know whether your intent is just to purely commit suicide here,” demands the priest. After a long pause, the prisoner replies, “What you call suicide, I call murder.”

You don’t have to agree with him – the priest doesn’t – to still be moved. The scenes that follow, of Sands’ final days in the prison hospital, are extremely hard to watch, yet they’re filmed with a gentle, valedictory point-of-view style that’s similar to ‘The Diving Bell and the Butterfly’ (another movie directed by an art-world figure, and a better one).

It’s ultimately Sands’ obstinacy, not his politics, that fascinates the filmmaker – that, and the prisoner’s willingness to use his own body as a canvas of protest. Where artists like McQueen build their statements by allusion and accretion, the movie’s Bobby takes away and takes away until there’s nothing left, and that absence, and the road there, are the meaning. ‘Hunger’ merely observes the process with something close to professional respect.