Veteran journalist David McKittrick was interviewed on BBC Radio 4’s ‘The Westminster Hour’ (26th July) and related a conversation with a Tory MP who thought the British government had won the hunger strike, though McKittrick soon corrected that perception. The following is an account of the exchange and is then followed by a full transcription from that part of the BBC programme by Olivia O’Leary. O’Leary interviewed various journalists and politicians about the Irish lobby within the British parliament – ‘Strangers in the Lobby’ – on how the role of Irish journalists was affected by the Troubles.

David McKittrick: “I went to London in 1981 – the hunger strikes were just ending at that point – ten republicans were dead. The British, they weren’t triumphant but they thought they had won. And I remember saying to a Tory MP – we were speaking at a conference and saying – who do you think won this? And he looked at me – didn’t know what I was talking about and I said – look, clearly Bobby Sands didn’t win the hunger strike, he’s dead. But the people that won it are his party Sinn Fein and his violent group the IRA. They won that because they’re doing very well. And I got incomprehension about this. They thought that the IRA had pitted itself against Margaret Thatcher and had been defeated. And I was saying – no there’s a big political backlash here – Sinn Fein is going to get into politics and it’s going to get a huge vote. So I was thinking this was a terrible time because the IRA is making advances. They thought that they had done very well in the hunger strikes and they thought, I think some of them thought that a corner had been turned and that terrorism would soon been defeated and the IRA would go away.”

Full transcription:

Olivia O’Leary: A vivid recollection from Brian O’Connell, a Westminster based London correspondent for the Irish state broadcaster, RTE.

Brian O’Connell: President Chirac had come to London. There was a news conference. I got a call from Downing Street asking me if I would go and ask a question about Northern Ireland. I said – what question would you like me to ask – and they said – well, any question you like.

Tony Blair: Right. Thank you all very much indeed for attending this press conference at the conclusion of the er …

BO: It was very, very crowded…

TB: … of the Anglo-French summit and …

BO: … but they’d kept me a seat in the front row. When it looked like the news conference was about to wrap up Tony Blair suddenly turned, pointed at me in the front row and said …

TB: Your question … which is … which I particularly wanted to give …

BO: Brian O’Connell for RTE, a question, Prime Minister on Northern Ireland …

BO: Because for him, Northern Ireland was a good news story.

Olivia O’Leary: Yes, Brian. The Prime Minister made sure that the Irish state broadcaster RTE’s London correspondent Brian O’Connell got a seat in the front row when Ireland was good news. But even when it wasn’t, in my time, when Dublin and London were at odds and the IRA was bombing Britain and British politicians the Irish media were always given special treatment. They were full members of the Westminster lobby with the briefings and the access given only to the British press. It’s a left-over from empire. After Irish independence the then pro-British Irish Times was allowed to remain in the lobby and it was felt unfair to leave the others out. Veteran foreign reporter Connor O’Cleary used to be The Irish Times London man.

C O’Cleary: The Irish Times correspondent and other Irish reporters could go to these lobby briefings and sit in with the British parliamentary correspondents. And we could also actually go into the lobby which is beside the chamber and get past the sergeant at arms past and accost MPs and ministers in the lobby. So we were sort of strangers in the House but right at the heart of the beast.

Kevin MacNamara: It was a relic of history and nobody was particularly going to want to make a particular issue out of it.

OO: Former MP and Labour Northern Ireland spokesman Kevin McNamara dealt with them for years. Were the Irish not regarded as strangers and potentially hostile strangers at that?

KM: No, I don’t think so… and I don’t think so because they were a particularly fine body of men and women. Everybody knew who they were there, they were very helpful, they were highly intelligent, they were fine ambassadors for their papers and for their country. Yes they represented Irish papers and that was known but they weren’t stuck out of … harps tattooed on their forehead or having to wear green armbands or anything. They were just taken as being part of the crowd, part of the media that was at the Palace of Westminster.

OO: But how easy was it for the Irish being at the heart of the old imperial power? Connor O’Cleary couldn’t quite forget his history.-

C O’Cleary: Well, you know you walk into the House of Commons and you’re surrounded by the statues of the villains of your historical make up.

OO: Like?

CO: Well, Churchill and people like that who, you know as an Irish Nationalist Churchill was not a very sympathetic figure. But at the same time I felt an enormous sense of privilege being able to walk into the lobby beside the chamber and stop members of parliament, even ministers and ask them questions about issues of the day. So that feeling of privilege overwhelmed any other feelings I might have.

OO: There was a sense of privilege and, you know, sometimes I wonder if we felt it too much. As an Irish reporter in the 70s coming into Westminster after the IRA had bombed Birmingham and Guildford I was struck by the fact that nobody ever associated me with those IRA attacks, nor should they. But I was so relieved and even seduced by that general British civility and acceptance that perhaps I didn’t question enough in wider coverage the convictions of Irish people for those bombings convictions that later proved to be appalling miscarriages of justice. Representing as we did the Irish media it was important not to feel too comfortable and journalists who asked awkward questions as Connor O’Cleary and others did occasionally DID feel uncomfortable.

CO: There were times when I felt a bit uneasy … the feeling that other journalists in the parliamentary lobby might be thinking that they would get more get more out of the Prime Minister’s press secretary on issues concerning Ireland if I wasn’t there. That there might be more of conspiratorial discussion about what policy was on Ireland if there wasn’t an eavesdropper like me sitting in the lobby.

OO: Still, Northern Ireland was the big story for us. Northern Ireland for three decades was ruled from Westminster and to have the ease of access that we did to Westminster decision-makers was extraordinary.

CO: One of the advantages of being a lobby correspondent was that one could be a member of the Newspaper Society which was an organisation to which London editors belonged and it held lunches for important politicians, occasionally the prime minister of the day. I remember Margaret Thatcher coming in once and seeing Aidan Hennigan of the Irish press and me and putting her arm round both of us and asking us how the elections were going in Ireland that day. So you had an intimacy there which you couldn’t get otherwise.

OO: And it was an intimacy that didn’t go unnoticed by other foreign journalists as David McKittrick, another Irish Times man remembers.

David McKittrick: People like the Commonwealth Association, they did resent the access we had and they had their own separate room but the thing was they weren’t allowed if my memory is correct into the main lobby but they also weren’t allowed into the daily briefings which are run by the Prime Minister’s spokespeople.

OO: So, we Irish got access to the heart of Westminster. But what did the British gain from us being there?

Kevin MacNamara: The other side of the coin. The question, the challenge to what was being put out by the publicity machines of the Northern Ireland Office or Stormont or of the British government. The fact that there were people there saying you know – hey – it’s not quite like that – just look at this. You only just have to look at the struggle that we had to try and get equality and fair employment and things like that established in the north, how much more difficult that would have been if there hadn’t been other people there questioning what was going on in the north and it wasn’t left to a small group of mainly Irish descent members of the Labour party, a couple of liberals who were raising these issues and the fact that there was a lobby there of Irish journalists meant that we weren’t cranks, that we were representing and showing that there were other opinions and other issues which had to be raised.

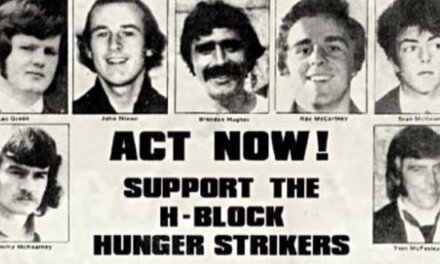

DM: I went to London in 1981 – the hunger strikes were just ending at that point – ten republicans were dead. The British, they weren’t triumphant but they thought they had won. And I remember saying to a Tory MP – we were speaking at a conference and saying – who do you think won this? And he looked at me – didn’t know what I was talking about and I said – look, clearly Bobby Sands didn’t win the hunger strike, he’s dead. But the people that won it are his party Sinn Fein and his violent group the IRA. They won that because they’re doing very well. And I got incomprehension about this. They thought that the IRA had pitted itself against Margaret Thatcher and had been defeated. And I was saying – no there’s a big political backlash here – Sinn Fein is going to get into politics and it’s going to get a huge vote. So I was thinking this was a terrible time because the IRA is making advances. They thought that they had done very well in the hunger strikes and they thought, I think some of them thought that a corner had been turned and that terrorism would soon been defeated and the IRA would go away.

OO: The Irish left their mark. One Irish journalist, disgusted by Britain’s small drinks measure established what he christened ‘the family measure’ still to be had at Westminster. Indeed it was often outside the formal channels that the Irish made their presence felt at the bars and the restaurants around the outside the House of Commons and as the Guardian’s parliamentary sketch writer Simon Hoggart remembers, at the Irish Embassy.

SH: The Irish affairs department as represented through the embassy in Britain never ever attempted to use direct propaganda, never ever attempted to say well this is what we think you’ve got to understand our point of view. They used a very, very different strategy altogether which was extremely successful. They invited us to parties. Not just because we were going to get drunk, that wasn’t the point at all. But they were able to bring journalists and politicians to the Irish embassy where they met not only Irish diplomats but people from Ireland, writers, actors generally the whole cultural life of Ireland as it is lived very richly in London. And so what we were left with was the impression that Ireland far from being a bunch of criminals who went around murdering people and blowing up people were a bunch of cultured, thoughtful, literate, civilised people and this I think helped to keep the British government and British politicians as well as the British press very much more on the Irish side than would otherwise have been the case. It was a brilliant piece of p.r. basically by the Irish using Ireland as the best publicity that the Irish government could possibly have, and it worked triumphantly.

OO: Veterans of the Irish hospitality war like Hoggart worked out counter-strategies.

SH: I always stick to the Guinness because it means that if I’m going to have another drink I have to actually leave the conversation I’m in, walk to the other end of the room and get another drink, which slows me down quite a bit. It’s the only possible strategy for dealing with the Irish Embassy party which I may say are without doubt the most loved and the most popular of all embassy parties in London.

OO: That good cheer and good publicity were needed when the troubles and the headlines were at their worst. But ironically as things improved and the peace process took hold the story became more complex. RTE’s man Brian O’Connell explains.

BO: I remember one instance when I asked at a lobby briefing some technical question to Alastair Campbell about a meeting that the then Taioseach Bertie Ahern had had with Tony Blair and what had come out of it and the understanding – Bertie Ahern’s understanding was obviously at odds with Tony Blair’s understanding of what had happened at the meeting. Alastair Campbell answered the question as best he could and afterwards on the way out he accosted me and said – for God’s sake don’t do that – and I said – it’s a perfectly legitimate question to ask. He said – No, no I’m not saying don’t ask me the question, but don’t ask in front of them – he said pointing over his shoulder at all the other lobby correspondents disappearing – he said, – because now they think there’s a story in it. Now I’ve got to go and talk down that story. It just goes to illustrate how Northern Ireland really had to be put under their noses before they would agree to run it. Partly because they were afraid of it and partly because they didn’t really understand it anyway.

OO: The change in Northern Ireland could not have happened without the change first in relations between London and Dublin. That has transformed the way that both countries see one another. And it’s changed the job of the Irish lobby at Westminster.

David McKittrick: It used to be that the Irish were forever saying to the British – you should change your policy you need to do a bit more of this and a bit more of that. What we’ve had for the last ten years is really a confluence of interest and a confluence of approach. You have London and Dublin, disagreeing on various issues, but on none of the big major issues. They both got together in the peace process, they both regarded the peace process as the thing to do, they both regarded it as wholeheartedly in their own interests and they both pursued it. And in my day there wasn’t a sense of partnership. But for the last ten years there has been an amazing sense of London/ Dublin partnership – something entirely new, something that has transformed Anglo/Irish relations.

OO: Westminster for all its recent scandals is still a place where history is made and where much of Irish history has been made. And Irish journalists who’ve worked there have found that it still has something to teach them.

OO: I certainly gained a greater appreciation of the power of oratory to settle big national issues. I also learned that Ireland wasn’t the number one issue in the minds of British politicians every hour of the day as one might be inclined to think looking at it from the other side of the Irish Sea.

O O’Leary: And that’s true. It was a salutary lesson to us coming from Ireland to find how little we figured in the great British scheme of things. Tony Blair was an exception to that and his efforts are reflected in Northern Ireland today. The process of peace there has allowed Irish people and Irish journalists at Westminster to move away from the old wounds and concentrate on a more normal relationship with our nearest neighbour on ordinary things like trade, on relations within the EU, on the sporting and cultural and family links that bind all of us on these islands. We’re not such strangers any more, you see. Maybe we never really were.