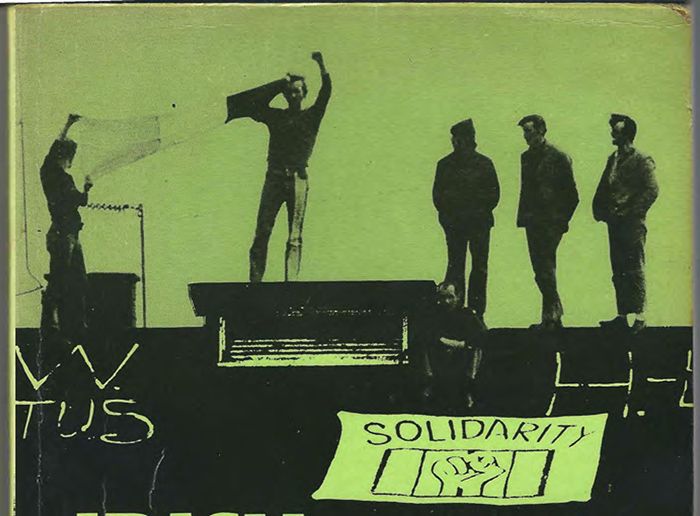

In his most recent weekly column in the Andersonstown News the former President of Sinn Féin and ex-prisoner, Gerry Adams, reviewed The Comrades. The book has sold out and is now being reprinted. (Featured photograph is of Republican POWs in England protesting on prison roof.)

Next week will mark forty years from the end of the 1981 hunger strike. Much has been written this year and many events have taken place to remember those who died. For me Ten Men Dead by David Beresford and Nor Meekly Serve My Time written by the prisoners themselves (including surviving hunger striker Laurence McKeown), remain two of the outstanding books of that period. Jim McCann’s 6000 Days is a very welcome and amazing recent addition to these publications. A must read book.

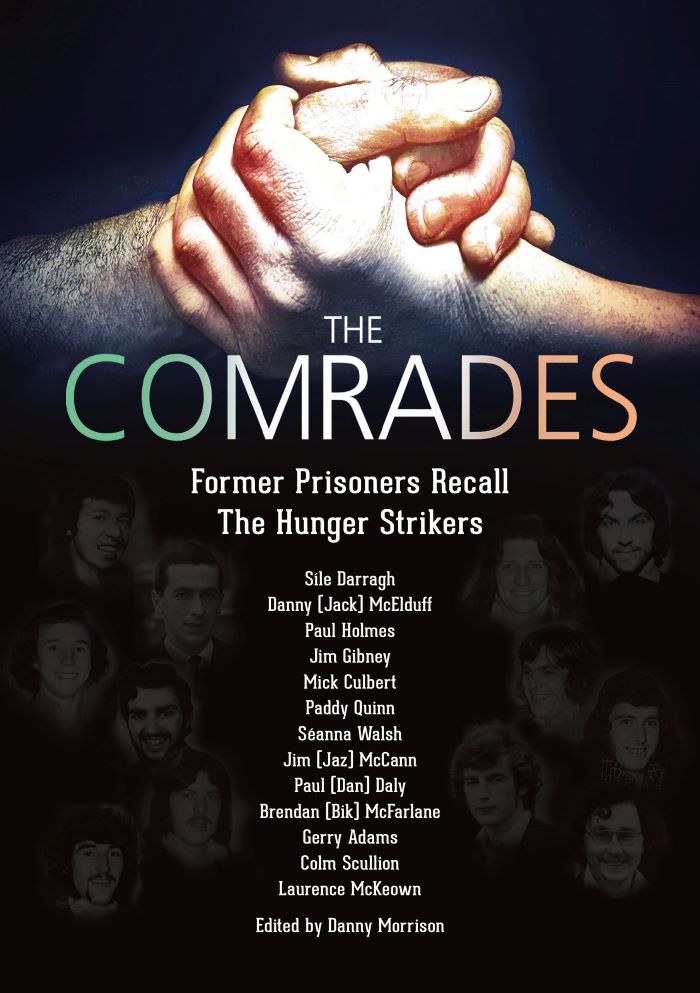

So too with another new book—The Comrades—just published by An Fhuiseog as part of the work of the ’81/’21 Committee. This collection of reflections provides a rare insight into the twelve republican prisoners who died on hunger strike during the most recent phase of the long struggle for Irish freedom. Padraic Wilson was the dynamo behind its publication and Danny Morrison edited it.

1981 was a watershed year in our history. The events of that year and the years leading to it are generally well known: the British decision to end political status; its efforts to criminalise the republican prisoners and through them the struggle; the heroic resistance of the women in Armagh Jail and the men on the blanket in the H-Blocks, and the support of families and communities across this island and internationally who rallied in support of the hunger strikers.

The Comrades deals less with the politics and more with the humanity of the hunger strikers. It is a powerful piece of work. It is a selection of accounts of each of the hunger strikers by those who knew them. The writers were all prisoners and lived through those difficult years. The emotion and memories that The Comrades evoke were evident last week at two events to launch the book. One in the Andersonstown Social Club and the one I attended and spoke at in the Tí Chulainn Centre in South Armagh.

Laurney McKeown who spent seventy days on the hunger strike writes about Mickey Devine. Paddy Quinn who was forty-seven days on hunger strike writes about Raymond McCreesh. Both former prisoners were in Tí Chulainn. And because we were in South Armagh I thought it appropriate to focus my remarks on Paddy Quinn and on his comrade Raymond McCreesh with whom he was captured in 1976.

I met Paddy in August 1981 when Own Carron, Seamus Ruddy and I went in to the prison hospital to speak to the hunger strikers and to tell them that if they chose to end the strike that we would support their decision.

Paddy started the hunger strike on the 15 June and he was the eleventh hunger striker. During the meeting—which included Laurney, Paddy, who was sitting in a wheel chair, told us that his sight had gone. I went and spoke to him privately.

Paddy said to me, ‘Ná bac. Lean ar aghaidh.’ (‘Don’t bother. Keep going.’)

Some years later in an interview Paddy recalled, ‘I wouldn’t give up. Maggie Thatcher wasn’t going to criminalise me.’

Paddy explained how painful the hunger strike was.

‘I could feel this terrible pain. A medical orderly was helping me to breathe, but I was hallucinating. I could hear the noise in my throat, gasping for breath. I was watching the deterioration of my body, thinking, “I have to do this; ‘’m going to keep going.”

‘It was just pain, day after day. Then one day I went for a shower, I collapsed in the shower, then there was the sickness. That was maybe after forty-three days, in and out of consciousness at that stage. I had reached that point that I was looking forward to death. I felt a real sense of contentment. I had accepted I was going to die and I was happy with my decision.

‘If the British had succeeded in criminalising us, we would never have got over it,’ says Paddy. ‘If Sinn Féin had remained hard-line and military, then I think the sacrifices made on the hunger strike would have been a complete waste. It was Sinn Féin going into politics that made it worthwhile.’

Paddy subsequently had to have a kidney transplant. His eyesight was damaged by the hunger strike. When asked if he had any regrets he said: ‘I remember somebody saying to me once, “You lost ten years.” I said, “In those ten years I probably had more experience than you’ll ever have.”’

RAYMOND

In his account about Raymond McCreesh Paddy remembers his friend and his decision to go on the hunger strike.

‘From the start of his protest Raymie had not taken a visit with his family or anyone else because he would not put on the “monkey suit.” I often think of how hard it must have been for Raymie and his mother, on their first visit in four years when the news he had to convey to her was that he was going on hunger strike… I was in the washroom in the shower when one of my comrades came in. He told me that news had just come through that Raymie had died a short time earlier.

‘I was glad I was standing in the shower. It meant that neither the screws nor anyone else could see the tears that I shed for my comrade and friend Raymond McCreesh.’

The Comrades is an evocative, inspiring, emotionally-moving account of the lives of twelve amazing men.

Laurence McKeown—a very fine writer and poet—in his essay in the book about Mickey Devine sums up the spirit of selflessness and courage that was and is the story of the 1981 hunger strike.

‘Regardless of our individual pasts, family histories, and the various routes we took that eventually led us to the H-Blocks, we became a ‘family’ in prison. A family of blanket men. We didn’t identify those on hunger strike as being either IRA Volunteers or INLA Volunteers. It didn’t matter who they were, what organisation they belonged to, what part of the country they were from, what they were charged with, or how long they were serving. They were blanket men. They were friends. They were brothers. They were Bobby, Frank, Patsy, Raymond, Joe, Martin, Kevin, Kieran, Tom and Mickey.’

In a final tribute to Mickey Devine, Laurny’s poem Red Mick is an appropriate conclusion to the humanity and compassion and love which was as much a part of the prison protests as the politics.

For I believe that in the H-Block you found

Something to love and live for

A place to give what was yours to offer

And not be judged by societal norms,

Exalting the few and damning the multitude.

And you loved and lived that so much

That you loved and lived it

To death.

– GERRY ADAMS

______________________________________________________________

Tribute to Patsy, Mickey & Comrades

The poem below was written in 1981 by Fionnbarra Ó Dochartaigh, a founding member of the Civil Rights Movement and one of the organisers of the civil rights march in Derry which was attacked by the RUC in Duke Street on 5 October 1968. Fionnbarra died just weeks ago, in early September.

CAIRDE CRÓGA GO BRÁCH

(Brave Friends Forever)

O’re James Connolly House, the black flag flew

While ’neath it wept comrades old and new

Hundreds lined in columns long

To bid a last farewell to our martyred sons.

Filing past each flower-decked bier

The common people, sighed, ’mid tears

For two workers’ sons had come back home

To we Bogside folk, forever, each our own.

Like hundreds, naked, lay in jail

Each cell their tomb, a sole blanket grey

Comrades all, on protest stayed

Neither to meet, nor, ‘Hello’ say.

For four long years in solitude

No books, or papers, ever to read

The outside world was far away

Even God’s sunlight, denied, each day.

They cried for justice, but few took heed

The rich man as ever, stayed aloof

The clerics, mainly they were deaf

As politicians like the ostrich stood.

When all other means, did not prevail

On hunger strike went ten, some, for o’re sixty days

Yes, freedom came, but with it death

While the May Flower blooms, we shan’t forget.

- Fionnbarra Ó Dochartaigh, Samradh, 1981, Doire Colmcille