THE HUNGERSTRIKERS

Background to the Hunger Strikes

In May 1972, a hunger strike commenced in Belfast Prison, which IRA prisoners ended 35 days later when British Direct-Ruler William Whitelaw gave in and granted ’special category status’, that is political status to political prisoners. From then, until 1976, many thousands of Irish men and women served their prison sentences under this special category regime in the cages of Long Kesh, and in A-Wing of Armagh women’s prison. Between the years 1971 and 1975 thousands of additional prisoners, interned without trial, had a similar status in Armagh, Magilligan, Belfast Prison, the prison-ship Maidstone, and Long Kesh.

In May 1972, a hunger strike commenced in Belfast Prison, which IRA prisoners ended 35 days later when British Direct-Ruler William Whitelaw gave in and granted ’special category status’, that is political status to political prisoners. From then, until 1976, many thousands of Irish men and women served their prison sentences under this special category regime in the cages of Long Kesh, and in A-Wing of Armagh women’s prison. Between the years 1971 and 1975 thousands of additional prisoners, interned without trial, had a similar status in Armagh, Magilligan, Belfast Prison, the prison-ship Maidstone, and Long Kesh.

The existence of thousands of prisoners, interned and sentenced under a regime which recognised them as political prisoners, coupled with the popular support for the armed struggle, forced the British government, after some earlier political and military miscalculations, to instigate a number of classical counterinsurgency measures. Primarily, the objective was to isolate those engaged in the resistance struggle from their support and to ‘normalise’ life in the Six-County state.

CRIMINALISATION

This attempted ‘isolation and normalisation’ policy took on a number of forms, all interlocked. There were various strategies adopted to create an illusion of political normalisation, the so-called ‘primacy of the police’, the gradual withdrawal of British army units and the Ulsterisation of British military forces were all tactically designed to isolate those engaged in struggle. This criminalisation attempt was part of the overall effort to project the resistance struggle as a criminal conspiracy and ran parallel with a propaganda thrust which saw the use of such terminology as ‘paramilitaries, Godfather, mafia’ etc, etc, by British government spokespersons.

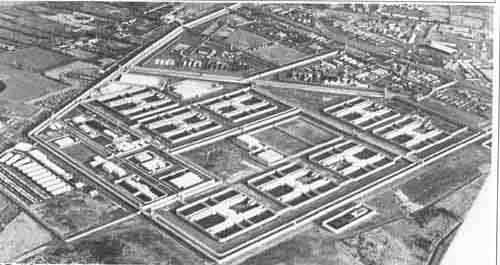

A major obstacle to this criminalisation policy was the fact that almost 2,000 prisoners, recognised by the British government as political prisoners, were still held in British prisons, which directly contradicted the British government’s propaganda claims. Long Kesh, by name and appearance was known worldwide as a concentration camp and the large number of political prisoners drawn from all over the Six Counties enjoyed, through family, community and local connections, maximum support.

In January 1975, a British commission (The Gardiner Commission) made a number of important recommendations. These included the phasing-out of political status and the ending of internment. Long Kesh had already been renamed HMP The Maze. A 50% remission scheme was introduced to accommodate the release of sentenced prisoners and the internees were released.

An arbitrary date, March 1st, was set and the British declared that anyone arrested after that date would not be treated as political prisoners and would serve their sentences in new cellular accommodation. The H-Blocks, designed to maximise the control of prisoners in four small wings of 25 single cells (instead of the traditional large huts), were born. In British terms, the strategy was simple. Outside the prison, however, the situation started to change, resistance recommenced and without the benefit of internment orders, the British Government employed new ‘legal’ methods to intern their opponents and to demoralise an uncompromising population. Castlereagh torture centre came into its own, rules of evidence were changed, extra Diplock (non-jury) courts were brought in, judges were appointed and the H-Block conveyor-belt went into full gear. Now instead of internment the British had a legal-looking process of arrest, charge, remand, trial and sentence. That the arrests were arbitrary, the charges based on forced confessions, the remands lengthy, the trials farcical and the sentences totally unjust was incidental,. The propaganda machine adequately covered all that. At least in the beginning.

An arbitrary date, March 1st, was set and the British declared that anyone arrested after that date would not be treated as political prisoners and would serve their sentences in new cellular accommodation. The H-Blocks, designed to maximise the control of prisoners in four small wings of 25 single cells (instead of the traditional large huts), were born. In British terms, the strategy was simple. Outside the prison, however, the situation started to change, resistance recommenced and without the benefit of internment orders, the British Government employed new ‘legal’ methods to intern their opponents and to demoralise an uncompromising population. Castlereagh torture centre came into its own, rules of evidence were changed, extra Diplock (non-jury) courts were brought in, judges were appointed and the H-Block conveyor-belt went into full gear. Now instead of internment the British had a legal-looking process of arrest, charge, remand, trial and sentence. That the arrests were arbitrary, the charges based on forced confessions, the remands lengthy, the trials farcical and the sentences totally unjust was incidental,. The propaganda machine adequately covered all that. At least in the beginning.

The architects of the new policy to criminalise those who resisted and portray prisoners as ordinary criminals, failed to take into account the resistance of a new generation of political prisoners, those sentenced after March 1st. They refused to accept the new regime, refused to cooperate with the prison guards or to accept prison discipline. They refused to wear the prison uniform, were denied thier own clothes, and wore only a blanket. As their numbers increased and the blanket protest strengthened, news of beatings, deprivations and maltreatment began to leak out of the H-Blocks of Long Kesh and the women’s prison in Armagh.

BLANKET PROTEST BEGINS

In March 1978, 18 months after the start of the blanker protest, with over 300 prisoners on protest, the prison administration stepped up the beatings and harassment and forced the blanket men on to the no-wash, no-slop out protest. This was to last for a full three years and arose essentially because the men were refused washing or toilet facilities or were beaten when they left their cells. The same thing was to happen later in Armagh in February 1980 when the prison administration attacked the women political prisoners, assaulting them and withdrawing toilet facilities.

In March 1978, 18 months after the start of the blanker protest, with over 300 prisoners on protest, the prison administration stepped up the beatings and harassment and forced the blanket men on to the no-wash, no-slop out protest. This was to last for a full three years and arose essentially because the men were refused washing or toilet facilities or were beaten when they left their cells. The same thing was to happen later in Armagh in February 1980 when the prison administration attacked the women political prisoners, assaulting them and withdrawing toilet facilities.

The majority of protesting prisoners, both men and women, were in their late teens or 20s and over 80% were imprisoned solely on the strength of forced confessions. They were refused from the beginning of their sentences all exercise facilities, reading or writing material, and access to radio or newspapers. Kept in cells on a punishment diet, with loss of all remission and without furniture, they were constantly beaten and harassed. Sinn Féin and Relatives’ Action Groups began a protest campaign, mostly confined to the Six-Counties, on the prisoner’s behalf.

CARDINAL O FIAICH VISITS H-BLOCKS

It was not until Cardinal, then Archbishop, O Fiaich, visited the prisoners on July 31st, 1978, and condemned the conditions under which the prisoners were being held, that greater public interest increased. He said: “Having spent the whole of Sunday in the prison, I was shocked at the inhuman conditions prevailing in H-Blocks 3,4 and 5 where over 300 prisoners were incarcerated. One would hardly allow an animal to remain in such conditions, let alone a human being. The nearest approach to it that I have seen was the spectacle of hundreds of homeless people living in sewer pipes in the slums of Calcutta. The stench and filth in some cells, with the remains of rotten food and human excreta scattered around the walls, was almost unbelievable. In two of them I was unable to speak for the fear of vomiting. The prisoners’ cells are without beds, chairs or tables. They sleep on mattresses on the floor, and in some cases I noticed they were quite wet. They have no covering except towel or blanket, no books, newspapers or reading material except the Bible (even religious magazines have been banned since my last visit), no pens or writing material, or TV, or radio, no hobbies or handcrafts, no exercise or recreation. They are locked in their cells for almost the whole of every day and some of them have been in this condition for more than a year and a half.”

Public interest had also been aroused by the Amnesty International report of June 1978, which stated categorically that: “Maltreatment of suspected terrorists by the RUC, has taken place with sufficient frequency to warrant establishment of a public inquiry to investigate it”.

However, the plight of the H-Block and Armagh prisoners again faded to some degree from the public view, until the establishment of the National H-Block/Armagh Committee in October 1979. This committee, elected from a broad-based campaign, advocated, with endorsement of the prisoners, five basic demands whose implementation would resolve the prison deadlock:

However, the plight of the H-Block and Armagh prisoners again faded to some degree from the public view, until the establishment of the National H-Block/Armagh Committee in October 1979. This committee, elected from a broad-based campaign, advocated, with endorsement of the prisoners, five basic demands whose implementation would resolve the prison deadlock:

The five demands were:

(1) No prison uniform;

(2) No prison work;

(3) Free association;

(4) Full remission;

(5) Visits, parcels, and recreational/educational facilities.

In March 1980 Cardinal O Fiaich again visited the prison and the following day he and Bishop Edward Daly met Direct-Ruler Humphrey Atkins for talks to attempt to settle the crisis, especially since the blanket men were now advocating hunger strike as a way out of the deadlock.

In an attempt to create an atmosphere conductive to a settlement and to take pressure off the British administration, the IRA ceased its attacks on prison officials. These talks dragged on for over six months before Cardinal O Fiaich and Bishop Daly had to admit they were getting nowhere.

FIRST HUNGER STRIKE BEGINS

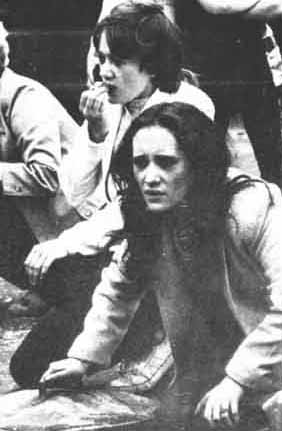

The blanket men and protesting women prisoners, totally exasperated, finally commenced hunger strike on October 27th, 1980. The fist H-Block hunger strike that was to last 56 days saw the greatest nationalist mobilisation in Ireland since the early days of the civil rights/anti-internment campaign. That peaceful and disciplined campaign, organised by the National H-Block/Armagh Committee, attracted on a single issue scores of thousands of people and united people of different political persuasions. The campaign itself came under attack from British and pro-British elements and campaign leaders John Turnley, Miriam Daly, Noel Little and Ronnie Bunting were murdered and Bernadette and Michael McAliskey were wounded.

The hunger strike ended on December 18th when the British government presented to the seven men who had fasted 53 days two documents. The three women hunger strikers ended their hunger strike the following day. On Thursday afternoon of December 18th, as the condition of hunger-striker Sean McKenna rapidly deteriorated, the British minister in charge of the Six Counties, Direct Ruler Humphrey Atkins, suddenly and without public explanation postponed a statement he had been due to make to the British parliament and ensured that it was delivered to the seven hunger strikers in the prison hospital along with a 34-page document entitled Regimes in Northern Ireland Prisons, Prisoners day to day life with special emphasis on Maze.

This document was new to the men and to the general public and was a major elaboration of how far the British government had gone in meeting the political prisoners’ five demands. “If they choose to live, the conditions available to them meet in a practical and humane way the kind of things they have been asking for”, said Atkins.

The fact that a British cabinet minister postponed a parliamentary statement to send it to protesting republican prisoners in order to seek a settlement to the 53-day-old hunger-strike, was a unique act of political recognition in itself and the delivery of the 34-page document reinforced this political recognition for up until then there had been no bending from the British government apart from one incident. On Wednesday, December 10th, when a senior member of the colonial Northern Ireland Office, a Mr Blellock, met the seven H-Block hunger strikers in the prison hospital and read out to them the prison reforms that were then available but refused to answer questions or negotiate with Brendan Hughes, former O/C of the blanket men.

The delivery of the document and the ending of the hunger-strike ushered in a new atmosphere and Bobby Sands, the blanket men’s O/C, was given freedom to liase and meet with the hunger strikers in the prison hospital, and each of the blanket Block O/Cs, and it was with him that the jail governor met directly, thus conferring recognition of the republican command structure. This recognition was reinforced when on Friday, December 19th, all of the H-Block O/Cs were brought out of their blocks for a further meeting with Bobby Sands in H-Block 3. Bobby Sands himself publicly expressed satisfaction at the new era of cooperation inside the jail, unprecedented since the British government embarked upon its policy of criminalisation in March 1976.

However, to the dismay of the prisoners, within days the atmosphere in the prison changed as soon as the spotlight shifted away from the jail. All the document’s phrases about the situation not begin static; work not being interpreted narrowly and the prison regime being progressive, humane and flexible were soon shown not to be worth the paper they were written on.

The blanket men had hoped to move about 30 men off the blanket and no-wash protest before Christmas Day but were stopped by Governor Hilditch who told Bobby Sands that nobody would be moving anywhere until they put on prison-issue clothing and conformed. In Armagh Jail, where women are allowed to wear their own clothes, George Scott the governor refused even to discuss with prisoners the question of self-education classes as outlined in the document.

HUMPHREY ATKINS RENEGES

On January 9th, in the British Parliament, Humphrey Atkins publicly reneged on his December 18th statement by reversing the order in which the men received their own clothes.

The prison administration tried to force the men to unconditionally end their protest but at a further meeting between all the H-Block O/Cs on January 11th it was decided to attempt in a step-by-step process the de-escalation of the protests in a principled fashion. Thus, following a period in which the prisoners cooperated to their utmost with a stubborn regime, on January 27th 96 prisoners smashed up cell furniture in a fit of frustration. The reaction from the prison administration was swift and brutal. Over 80 prisoners were assaulted, beaten in wing shifts, left overnight without bedding or blankets or drinking water, refused toilet facilities and had meals interfered with or withdrawn altogether.

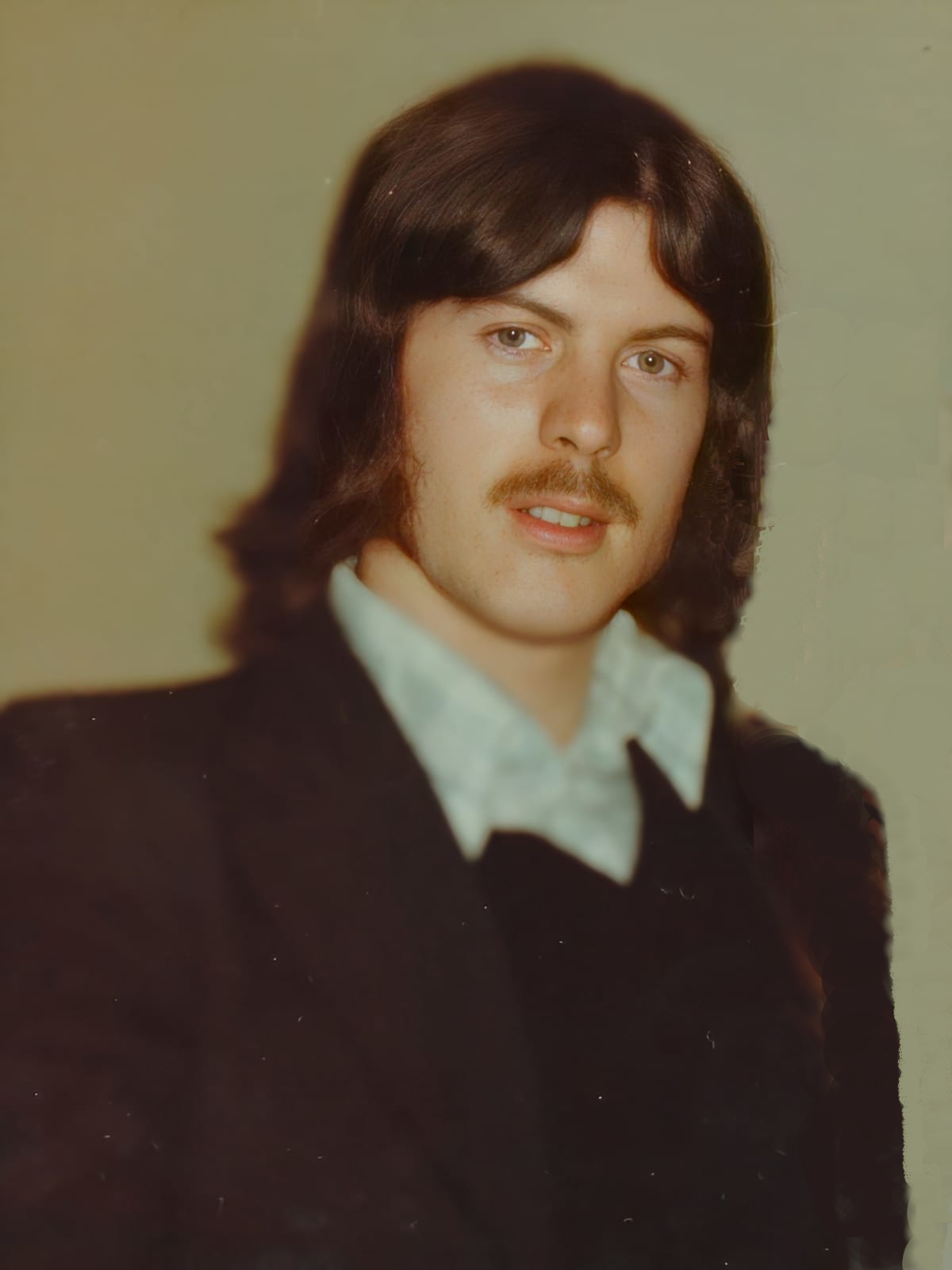

It was back to square one. Despite calls from the blanket men to those who had appealed to them to abandon their hunger strike, no one, from Bishop to politician, spoke out. Then on March 1st, Bobby Sands commenced hunger strike. In a statement announcing the commencement of the hunger strike the political prisoners said:

“We the republican POWs in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh, and our comrades in Armagh Prison, are entitled to and hereby demand political status, and we reject today as we have consistently rejected every day since September 14th, 1976, when the blanket protest began, the British government’s attempted criminalisation of ourselves and our struggle.

“Five years ago this day, the British government declared that anyone arrested and convicted after March 1st, 1976, was to be treated as a criminal and no longer as a political prisoner. Five years later we are still able to declare that that criminalisation policy, which we have resisted and suffered, has failed.

“If a British government experienced such a long and persistent resistance to a domestic policy in England then that policy would almost certainly be changed. But no so in Ireland where its traditional racist attitude blinds its judgement to reason and persuasion.

“Only the loud voice of the Irish people and world opinion can bring them to their senses and only a hunger strike, where lives are laid down as proof of the strength of our political convictions, can rally such opinion and present the British with the problem that, far from criminalizing the cause of Ireland, their intransigence is actually bringing popular attention to that cause.

“We have asserted that we are political prisoners and everything about our country, our arrest, interrogations, trials and prison conditions, show that we are politically motivated and not motivated by selfish reasons or for selfish ends. As further demonstration of our selflessness and the justness of our cause a number of comrades, beginning today with Bobby Sands will hunger strike to the death unless the British government abandons its criminalisation policy and meets our demand for political status.”