Nâzım Hikmet was once declared by the Turkish state as a traitor. But almost fifty years after his death, this year the Deputy Prime Minister Cemil Cicek announced that “Turkey is restoring the citizenship of its most famous 20th century poet Nâzım Hikmet”. Mick Hall, in a feature solicited by the Bobby Sands Trust, examines the life of this great poet.

Nâzım Hikmet was once declared by the Turkish state as a traitor. But almost fifty years after his death, this year the Deputy Prime Minister Cemil Cicek announced that “Turkey is restoring the citizenship of its most famous 20th century poet Nâzım Hikmet”. Mick Hall, in a feature solicited by the Bobby Sands Trust, examines the life of this great poet.

Nâzım Hikmet, Communist Poet

By Mick Hall

Nâzım Hikmet was truly a man of his age, and when reading his work it is easy to see why it enraged the bureaucrats who oversaw the Turkish State. For the more his jailers turned the screw the more he rebelled against their brutality and proclaimed for all to see the beauty in the world and that within his fellow man.

Born in 1901 into a wealthy bourgeois family which had strong connection within the Ottoman Court, his grandfather belonged to the liberal Mevlevi order of Islam (Sufi), whose religious rituals included expressing their faith through dance. Throughout the Ottoman period the Mevlevi order was famous for its poets and musicians. They also helped man the upper echelons of the bureaucracy of the Ottoman Empire and Caliphate.

Nâzım Hikmet was educated in the tradition of an upper class Turkish child of his day. His schooling was in French and at 16 he entered a prestigious naval academy, graduating in 1918. However, after being posted to a war ship he became ill and having spent a year in hospital he was discharge from the Navy in 1920 for health reasons.

At the end of WW1, the Ottoman Empire, which had sided with Germany in that needless, bloody conflagration, crumbled into dust and its capital, Istanbul, and much of modern day Turkey were occupied by the armies of the victorious Allies, who planned to carve up these lands between the UK, France, Italy and Greece, leaving the Turks only a small piece of land in central Anatolia.

Having become radicalized by ‘Ataturk’s’ (Mustafa Kemal’s) call to liberate Turkey from the foreign invaders, Hikmet wrote a poem called Gençlik, (Youth) which was a call to the younger generation to fight for the liberation of their country.

On 1 January 1921, Hikmet was able to make his way covertly from Istanbul to central Turkey with the help of an illegal organization which provided weapons to Mustafa Kemal’s emerging army, who were then based, along with the command of the resistance movement, at a small town called Ankara, which then was famous for sheep that produced angora wool; and today is the capital of the Turkish Republic.

The publication of Gençlik caused a stir amongst tens of thousands of young Turks, who were enthused by it to join the struggle to liberate Turkey from its foreign occupiers. When he arrived in Ankara, Nâzım Hikmet was summoned to meet Mustafa Kemal, who advised him, “In order to be modern, some young poets write theme-less poems. I advise you to write poetry with an aim.” Ataturk then arranged for Hikmet to work at the fledgling ‘Ministry of Education,’ probably realizing that he would be out of harm’s way and more valuable there than at the front, especially given that at the time Kemal had more men than he had arms to supply them with.

It was during this time that Nâzım Hikmet came into contact with people who spoke favourably about the Russian Revolution. That Lenin’s government had been the first to recognize Kemal’s provisional government must have further endeared the Bolsheviks to Hikmet.

Nevertheless, it was not only the town Ankara that was a backward and conservative place, so too were many senior members of Ataturk’s army, staffed as it was by men like Kemal who were former officers in the Ottoman armies, many of whom had been trained in staff colleges manned by teachers seconded from the Kaiser’s army. Thus word soon reached Ziya Hilmi, a senior official in the provisional government, about a group of young men who refused to attend the mosque and argued about left-wing radical ideas. It was one thing for Ataturk and his immediate entourage to push the political envelope wide, but quite another thing to allow all and sundry.

Whilst not unsympathetic to radical ideas himself, Hilmi knew that for Ataturk winning the war of liberation took precedent; and, he concluded, Hikmet would be safer abroad. Thus Hikmet and a fellow poet Vâlâ Nureddin went to Moscow to study and experience the Russian revolution at first hand. It was here he came under the influence of Vladimir Mayakovski, Meyerhold and other Soviet poets, musicians and artists who belonged to the Left Art Front.

Hikmet returned to Turkey in 1924, not long after the Turkish War of Independence had ended in a victory for Ataturk’s forces and the foundation of the Turkish Republic. But he was soon arrested for working on a leftist magazine. In 1926 he managed to avoid a police round-up of leftists by again going to Russia, where he continued writing poetry and plays.

A general amnesty allowed him to return to Turkey in 1928. By then he had joined the Turkish Communist Party, which had been outlawed, and he found himself under constant surveillance by the new Republic’s secret police and spent five of the next ten years in prison, on a variety of trumped-up charges. In 1933, for example, he was remanded in jail for putting illegal posters in a public place, but when his case came to trial it was thrown out of court for lack of evidence.

Meanwhile, between 1929 and 1936 he published nine books, five collections and four long poems that revolutionized Turkish poetry, flouting Ottoman literary conventions and introducing free verse and colloquial diction. While these poems established him as a major poet, he also published several plays and novels and to keep the wolf from the door he also worked as a bookbinder, proof-reader, journalist, translator, and screenwriter to support an extended family that included his second wife, her two children, and his widowed mother.

With Mustafa Kemal ‘Atatürk’ dead, the Turkish State, having failed to break Nâzım Hikmet’s political will, then decided to lock him away for good, by placing him before a drumhead court and on the night of 17 January 1938, he was arrested by the police. He was sent to the Military Court of the Military College Headquarters in Ankara to be tried for “provoking military personnel to rebel against their superiors.” He was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years, although the State was not done with Nâzım as it was determined to place a double lock on his cell door.

To ensure this happened he was then brought before the Military Court of the Naval Headquarters, charged with having “provoking naval soldiers to rebellion.” For this imaginary ‘crime’ the gallant admirals sentenced Nâzım Hikmet to a further 25 years.

Although feeling victorious they pared the 35 years down to 28 years and 4 months in total prison time. This sentence was approved by the Military Supreme Court on 29 December 1938 and Hikmet disappeared into the dark vault that was, and still is, the Turkish penal system.

Far from being silenced Nâzım Hikmet wrote ferociously for the next 12 years, smuggling new poems out of the jails on scraps of paper. On completing a poem he would read it to his friends amongst his fellow inmates who looked forward to these readings as they took them beyond the prison walls.

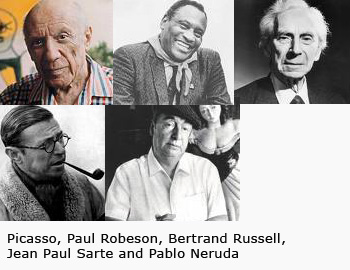

After WW2 ended a campaign to free Hikmet gradually built up steam, both within Turkey and abroad, where a committee was set up in 1949 to campaign for his release. It included the leading artist and writers of the day including the poet Pablo Neruda, Picasso, the singer Paul Robeson and intellectuals like Jean Paul Sarte and Bertrand Russell.

It was during this period that Hikmet engaged in an 18-day hunger strike to further pressure the Turkish authorities. On 15 July 1950, shortly after Turkey’s first ‘democratically’ elected government came to power, he was told by his lawyer that he was free at last.

However, the security services had not given up on him and within a short time of being released their persecution of him began again. Reluctantly Nâzım Hikmet was once again forced into exile. Given a house outside of Moscow, he travelled widely in Europe, Asia, Cuba and Africa, promoting his work and the causes he believed in. He died of a heart attack in 1963.

Whilst persecuted by the Turkish State in his own lifetime and his books and poems banned, Nâzım Hikmet is today revered by the overwhelming majority of the Turkish people. At the turn of the 21st century over 500,000 Turks signed a petition demanding that the government restore Hikmet’s citizenship. Ask any Turk who their nation’s greatest poet is and resoundingly they will reply Nâzım Hikmet, often quoting a verse of one of his poems to prove their love.

Sensing the public’s great love for the man and his work, Turkey’s political elite do likewise. Whether they be on the political left, centre or right, they now all sing the praise of this radical communist internationalist.

The current Islamic AKP government is no exception. Over 50 years after the Turkish State branded Hikmet a traitor and withdrew his citizenship, Deputy Prime Minister Cemil Cicek recently announced that “Turkey is restoring the citizenship of its most famous 20th century poet Nâzım Hikmet.”

Myself, I have absolutely no doubt that 50 years on, the Irish political elite will be glorifying Bobby Sands and, as with the aforementioned Turkish political elite, they will be doing so, for all the wrong reasons.

SOME ADVICE TO THOSE WHO WILL SERVE TIME IN PRISON

If instead of being hanged by the neck

You’re thrown inside

for not giving up hope

in the world, your country, your people,

if you do ten or fifteen years

apart from the time you have left,

you won’t say,

“Better I had swung from the end of a rope

like a flag” –

You’ll put your foot down and live.

It may not be a pleasure exactly,

but it’s your solemn duty

to live one more day

to spite the enemy.

Part of you may live alone inside,

like a tone at the bottom of a well.

But the other part

must be so caught up

in the flurry of the world

that you shiver there inside

when outside, at forty days’ distance, a leaf moves.

To wait for letters inside,

to sing sad songs,

or to lie awake all night staring at the ceiling

is sweet but dangerous.

Look at your face from shave to shave,

forget your age,

watch out for lice

and for spring nights,

and always remember

to eat every last piece of bread-

also, don’t forget to laugh heartily.

And who knows,

the woman you love may stop loving you.

Don’t say it’s no big thing:

it’s like the snapping of a green branch

to the man inside.

To think of roses and gardens inside is bad,

to think of seas and mountains is good.

Read and write without rest,

and I also advise weaving

and making mirrors.

I mean, it’s not that you can’t pass

ten or fifteen years inside

and more –

you can,

as long as the jewel

on the left side of your chest doesn’t lose it’s luster!

Nazim Hikmet – May 1949. Trans. by Randy Blasing and Mutlu Konuk (1993)

——————————————-

PLEA

This country shaped like the head of a mare

Coming full gallop from far off Asia

To stretch into the Mediterranean

THIS COUNTRY IS OURS.

Bloody wrists, clenched teeth

bare feet,

Land like a precious silk carpet

THIS HELL, THIS PARADISE IS OURS.

Let the doors be shut that belong to others

Let them never open again

Do away with the enslaving of man by man

THIS PLEA IS OURS.

To live! Like a tree alone and free

Like a forest in brotherhood

THIS YEARNING IS OURS.

—————————————

LETTERS FROM A MAN IN SOLITARY

1

I carved your name on my watchband

with my fingernail.

Where I am, you know,

I don’t have a pearl-handled jackknife

(they won’t give me anything sharp)

or a plane tree with its head in the clouds.

Trees may grow in the yard,

but I’m not allowed

to see the sky overhead…..

How many others are in this place?

I don’t know.

I’m alone far from them,

they’re all together far from me.

To talk anyone besides myself

is forbidden.

So I talk to myself.

But I find my conversation so boring,

my dear wife, that I sing songs.

And what do you know,

that awful, always off-key voice of mine

touches me so

that my heart breaks.

And just like the barefoot orphan

lost in the snow

in those old sad stories, my heart

– with moist blue eyes

and a little red runny rose-

wants to snuggle up in your arms.

It doesn’t make me blush

that right now

I’m this weak,

this selfish,

this human simply.

No doubt my state can be explained

physiologically, psychologically, etc.

Or maybe it’s

this barred window,

this earthen jug,

these four walls,

which for months have kept me from hearing

another human voice.

It’s five o’clock, my dear.

Outside,

with its dryness,

eerie whispers,

mud roof,

and lame, skinny horse

standing motionless in infinity

-I mean, it’s enough to drive the man inside crazy with grief-

outside, with all its machinery and all its art,

a plains night comes down red on treeless space.

Again today, night will fall in no time.

A light will circle the lame, skinny horse.

And the treeless space, in this hopeless landscape

stretched out before me like the body of a hard man,

will suddenly be filled with stars.

We’ll reach the inevitable end once more,

which is to say the stage is set

again today for an elaborate nostalgia.

Me,

the man inside,

once more I’ll exhibit my customary talent,

and singing an old-fashioned lament

in the reedy voice of my childhood,

once more, by God, it will crush my unhappy heart

to hear you inside my head,

so far

away, as if I were watching you

in a smoky, broken mirror…

2

It’s spring outside, my dear wife, spring.

Outside on the plain, suddenly the smell

of fresh earth, birds singing, etc.

It’s spring, my dear wife,

the plain outside sparkles…

And inside the bed comes alive with bugs,

the water jug no longer freezes,

and in the morning sun floods the concrete…

The sun-

every day till noon now

it comes and goes

from me, flashing off

and on…

And as the day turns to afternoon, shadows climb the walls,

the glass of the barred window catches fire,

and it’s night outside,

a cloudless spring night…

And inside this is spring’s darkest hour.

In short, the demon called freedom,

with its glittering scales and fiery eyes,

possesses the man inside

especially in spring…

I know this from experience, my dear wife,

from experience…

3

Sunday today.

Today they took me out in the sun for the first time.

And I just stood there, struck for the first time in my life

by how far away the sky is,

how blue

and how wide.

Then I respectfully sat down on the earth.

I leaned back against the wall.

For a moment no trap to fall into,

no struggle, no freedom, no wife.

Only earth, sun, and me…

I am happy.

Nazim Hikmet – 1938. Trans. by Randy Blasing and Mutlu Konuk (1993)

——————————————————————-

A SAD STATE OF FREEDOM

You waste the attention of your eyes,

the glittering labour of your hands,

and knead the dough enough for dozens of loaves

of which you’ll taste not a morsel;

you are free to slave for others-

you are free to make the rich richer.

The moment you’re born

they plant around you

mills that grind lies

lies to last you a lifetime.

You keep thinking in your great freedom

a finger on your temple

free to have a free conscience.

Your head bent as if half-cut from the nape,

your arms long, hanging,

your saunter about in your great freedom:

you’re free

with the freedom of being unemployed.

You love your country

as the nearest, most precious thing to you.

But one day, for example,

they may endorse it over to America,

and you, too, with your great freedom-

you have the freedom to become an air-base.

You may proclaim that one must live

not as a tool, a number or a link

but as a human being-

then at once they handcuff your wrists.

You are free to be arrested, imprisoned

and even hanged.

There’s neither an iron, wooden

nor a tulle curtain

in your life;

there’s no need to choose freedom:

you are free.

But this kind of freedom

is a sad affair under the stars.

Nazim Hikmet

————————————————–

THE STRANGEST CREATURE ON EARTH

You’re like a scorpion, my brother,

you live in cowardly darkness

like a scorpion.

You’re like a sparrow, my brother,

always in a sparrow’s flutter.

You’re like a clam, my brother,

closed like a clam, content,

And you’re frightening, my brother,

like the mouth of an extinct volcano.

Not one,

not five-

unfortunately, you number millions.

You’re like a sheep, my brother:

when the cloaked drover raises his stick,

you quickly join the flock

and run, almost proudly, to the slaughterhouse.

I mean you’re strangest creature on earth-

even stranger than the fish

that couldn’t see the ocean for the water.

And the oppression in this world

is thanks to you.

And if we’re hungry, tired, covered with blood,

and still being crushed like grapes for our wine,

the fault is yours-

I can hardly bring myself to say it,

but most of the fault, my dear brother, is yours.

Nazim Hikmet – 1947.Trans. by Randy Blasing and Mutlu Konuk (1993)

———————————————————–

LETTER TO MY WIFE

11-11-19933

Bursa Prison

My one and only!

Your last letter says:

“My head is throbbing,

my heart is stunned!”

You say:

“If they hang you,

if I lose you,

I’ll die!”

You’ll live, my dear-

my memory will vanish like black smoke in the wind.

Of course you’ll live, red-haired lady of my heart:

in the twentieth century

grief lasts

at most a year.

Death-

a body swinging from a rope.

My heart

can’t accept such a death.

But

you can bet

if some poor gypsy’s hairy black

spidery hand

slips a noose

around my neck,

they’ll look in vain for fear

in Nazim’s

blue eyes!

In the twilight of my last morning

I

will see my friends and you,

and I’ll go

to my grave

regretting nothing but an unfinished song…

My wife!

Good-hearted,

golden,

eyes sweeter than honey-my bee!

Why did I write you

they want to hang me?

The trial has hardly begun,

and they don’t just pluck a man’s head

like a turnip.

Look, forget all this.

If you have any money,

buy me some flannel underwear:

my sciatica is acting up again.

And don’t forget,

a prisoner’s wife

must always think good thoughts.

—————————————————————

LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT

Comrades, if I don’t live to see the day

– I mean,if I die before freedom comes –

take me away

and bury me in a village cemetery in Anatolia.

The worker Osman whom Hassan Bey ordered shot

can lie on one side of me, and on the other side

the martyr Aysha, who gave birth in the rye

and died inside of forty days.

Tractors and songs can pass below the cemetery –

in the dawn light, new people, the smell of burnt gasoline,

fields held in common, water in canals,

no drought or fear of the police.

Of course, we won’t hear those songs:

the dead lie stretched out underground

and rot like black branches,

deaf, dumb, and blind under the earth.

But, I sang those songs

before they were written,

I smelled the burnt gasoline

before the blueprints for the tractors were drawn.

As for my neighbors,

the worker Osman and the martyr Aysha,

they felt the great longing while alive,

maybe without even knowing it.

Comrades, if I die before that day, I mean

– and it’s looking more and more likely –

bury me in a village cemetery in Anatolia,

and if there’s one handy,

a plane tree could stand at my head,

I wouldn’t need a stone or anything.

Nazim Hikmet, 27 April 1953, Moscow, Barviha Hospital

————————————————————

I love my country . . .

I love my country . . .

I swung in its lofty trees, I lay in its prisons.

Nothing relieves my depression

Like the songs and tobacco of my country.

. . . and then my working, honest, brave people.

Ready to accept with the joy of a wondering child,

everything,

progressive, lovely, good,

half hungry, half full.

half slave . . .

(Memleketimi seviyorum [I love my country].

——————————————————————————–

Organized Rage

http://www.organizedrage.com/