The Bobby Sands Trust has welcomed the discovery of pictures of Bobby Sands taking part in the first political status protest in Belfast in August 1976, just two months before his arrest. The pictures have also been published in today’s Irish News. Bobby had only been released from Long Kesh in April 1976 where he had been a political prisoner. He was rearrested, six months later, in October 1976. After being sentenced to fourteen years he spent several years ‘on the blanket’ protest before leading the 1981 hunger strike when he and nine other comrades died.

The pictures came to light when a researcher, Ciaran Cahill, was working on the late Fr Des Wilson’s ‘People’s Archive’ in Springhill House, Ballymurphy. He was scanning negatives of photographs donated by Lelia Doolan. She was a keen photographer, a friend of Fr Des and chronicled life in Ballymurphy between 1974 and 1977 while studying for a PhD in Anthropology at Queens University.

When cataloguing the negatives Ciaran Cahill at first recognised Máire Drumm. When he developed them he remembered similar photographs by French photographer Gérard Harlay which were discovered and published in 2019. In fact, they are of the same march, the first of many, protesting against the British government’s withdrawal of political status.

A close-up of one photograph as the march proceeds down the Andersonstown Road shows Bobby Sands at the bottom right of the frame (he is carrying the Leinster flag, just out of view).

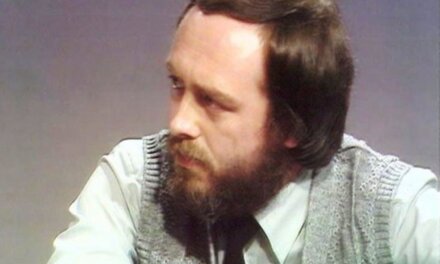

Another photograph of the platform party in Dunville Park is of the following people (left-to-right): Billy Donnelly (trade unionist), Bobby Sands, Kevin Carson (former prisoner), Jimmy Roe (deceased; former prisoner) and Geordie Bennett (deceased; former prisoner). Next is Máire Drumm, one of the speakers at the rally. She was arrested shortly afterwards, with others, and imprisoned for eighteen days for taking part in an ‘illegal procession’. She was assassinated a few weeks later in the Mater Hospital by gunmen dressed as medical staff. Next to Máire Drumm is Sinn Féin member Aindrias O Callaghan from Dublin, one of the guest speakers, and who in October would give the oration at Máire Drumm’s funeral in Milltown Cemetery. Next to O Callaghan is the late Jimmy Drumm (husband of Máire) and next to him is the late Joe Stagg whose brother Frank had died on hunger strike in Wakefield Prison in February 1976. Below Joe Stagg is Danny Morrison, editor of Republican News.

Danny Morrison, Secretary of the Bobby Sands Trust, said: ‘These photographs, from almost fifty years ago, are quite evocative, especially when one considers the tragic deaths of Máire Drumm and Bobby Sands. I had forgotten that I was covering the protest for Republican News and it was a surprise to see my younger self, then twenty-three. But even back then we instinctively knew that the attempt to criminalise the struggle for Irish independence, as in previous periods, would ultimately fail. However, we had no idea of the magnitude of the suffering to come, inside and outside the prisons, for all those entrapped by this cruel and vindictive British policy.’

Cork-born Lelia Doolan, who turned ninety last May, photographed many scenes in West Belfast and housing estates, including Sandy Row. She later became the head of light entertainment at RTÉ, artistic director of the Abbey Theatre and directed ‘Bernadette: Notes on a Political Journey’, a highly-praised documentary about Bernadette Devlin McAliskey.

The long term aim of Springhill Community House is the creation of The Fr Des Wilson interpretive centre, a permanent space for the People’s Archive in West Belfast that would accept donations of personal collections related to the conflict and community activism. It currently contains thousands of documents, recordings, negatives and photographs. It is about: the role of the Catholic Church in the conflict; Fr Des’s ecumenism; local activism; and his role along with others in international campaigns for equal rights and justice.

Collectively, this material tells the story not just of Ballymurphy, but wider West Belfast, and working class communities in the North. It is valuable historical evidence that offers an insight into communities often rendered voiceless by the powers-that-be.