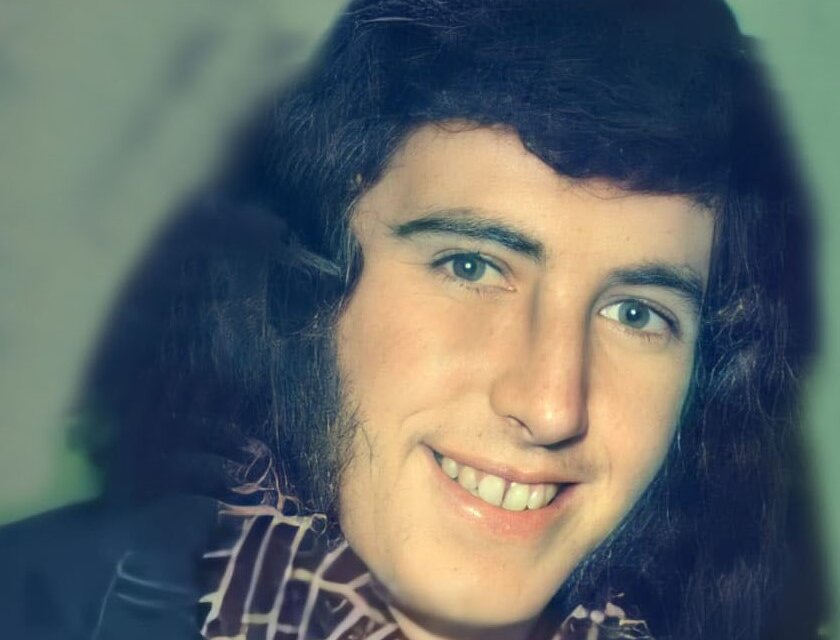

There were a number of commemorations held in Tyrone for the fortieth anniversary of Martin Hurson, the sixth H-Block hunger striker to die in 1981. Martin, from Aughnaskea, aged twenty-four, died forty six days into his hunger strike on July 13th, 1981, and is buried in the small graveyard behind St John the Baptish Chapel in Galbally.

Martin’s profile, first published by Sinn Féin in 1981, can be read here, though over the years much more detail has emerged in letters and photographs about Martin’s upbringing and from interviews with his friends and comrades, with more information about his prison experiences. In a forthcoming book, The Comrades, his friend from prison Paul ‘Dan’ Daly contributes a chapter about Martin.

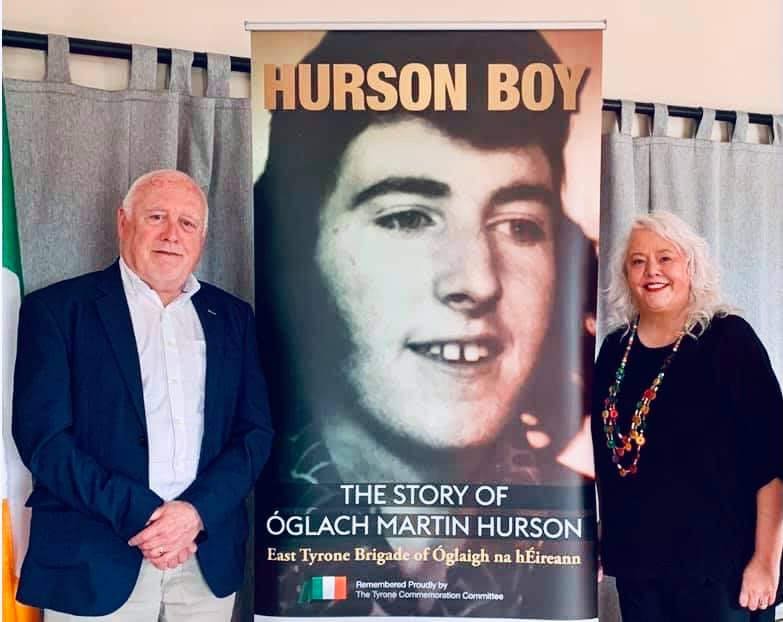

This week also saw the launch of Hurson Boy compiled by Nuala Donnelly on behalf of the Tyrone Commemoration Committee. The book launch can be watched here.

The book launch features Francie Molly, Sinn Féin Mid-Ulster MP, who was prominent in the National H-Block/Armagh Committee, and Danny Morrison, Secretary of the Bobby Sands Trust who wrote the Introduction to the book.

In this interview, one of the excellent series of podcasts by Guthanna ’81 | Voices of ’81, Nuala talks about her writing of the book.

Old news footage of Martin’s funeral – with the usual ‘health warnings’ – can be viewed here.

On Tuesday, Mass, attended by the Hurson large family circle, was said in memory of Martin in St John the Baptist church. Afterwards, Tyrone Commemoration Committee paid their respects by organising an event at Martin’s grave, which included a wreath-laying ceremony, the lowering of the national flag, and the playing of Martin Hurson by Gerry O’Glacain of the Irish Brigade. The main oration was delivered by Danny Morrison who said:

I’m honoured to be standing here today at the graveside of Martin Hurson and those of his comrades-in-arms, who laid down their lives on behalf of their people. Today, we also remember IRA Volunteer Willie Price from Brockagh who was killed in action on this date in 1984.

I never met Martin yet I feel I have known him. From his sisters and brothers, especially Brendan and Francie, from his friends and relatives, from the Tyrone men with whom I was in jail in the H-Blocks. From the way they speak about him with respect and admiration and awe. The stories and anecdotes about him. His sense of commitment to the struggle, his sense of humour, his love of family, of Bernadette, his love of Tyrone, his love for the Irish people.

He is remembered in the songs that honour him—and now in the book, Hurson Boy by Nuala Donnelly, remembered with all those evocative photographs which intensify the sense of his presence, the sense of our loss.

Martin grew up in a bitter, sectarian one-sided state that was built on injustice, on the suffering of my generation and that of our parents and grandparents. It had its Protestant B-Specials and its RUC to keep us down. It practiced discrimination in housing and employment to keep down our numbers and to ensure that the majority of those who emigrated where nationalists, and in this way ensure that there was a unionist majority in perpetuity.

I believe that what additionally fueled the anger and the explosion within Tyrone is the fact that Tyrone and Fermanagh were destined to be in a new 28-county state but were given away, against their wishes, by John Redmond who felt that unionism could be appeased and would act fairly. But this only encouraged unionist intransigence which went on to say, ‘what we have, we hold’, ‘not an inch’, and which boasted we are ‘a Protestant Parliament for a Protestant People.’

And it was that sectarianism of ‘not an inch’ which would ensure the eventual downfall of unionism. The rejection of civil rights; indeed, the suppression of the Civil Rights Movement, created the conditions for conflict and for armed struggle. Only this time, the RUC and the B-Specials, now constituted as the UDR, were supplemented by the might of the British Army.

Martin Hurson, like many young people, had had enough of being treated second-class in his own country.

It took tremendous courage to step forward to oppose the British government and its interference in our country. Make no mistake about it. IT is the real enemy—and without the British presence, without its interference, negotiations about the future of this country would be much easier.

Behind the unionist state was the British presence. They had mighty barracks, armoured cars, helicopters, flak jackets, superior firepower—and they had torture. They had judges they could rely upon to ignore the torture that took place in their barracks, such as that suffered by Martin. They had their prisons and their well-paid prison officers who were on big bounties and whose task it was to break the women in Armagh and the men in the H-Blocks.

Their theory was very simple. And very brutal. They thought: we cannot defeat the IRA on the outside so let’s break their men and women on the inside, by humiliating them, by torturing them, by criminalising them. We will break their morale, we will break the IRA, we will break their supporters and sap their will to resist, their will to fight, because in the jails they will have surrendered to our authority, to our might. The Brits are the original fools that Patrick Pearse spoke about, because, you see, the Brits have always confused ‘might’ with being ‘right’.

Bobby Sands wrote:

They lounge in might and glory

This empire once so grand.

But tank or gun they had not one

To break a blanket man.

And they could not break Bobby, Frank, Raymond, Patsy, Joe, Martin, Kieran, Kevin, Thomas or Mickey.

They took Martin and his comrades away. They took away their freedom, then their clothes, shoes and socks and locked them up for twenty-three hours a day. Then they took away the walk around the prison yard in fresh air, under blue skies. They took away their smokes – that small precious allowance of tobacco which in every prison steadies and calms nerves and makes the day endurable. They took away their beds. When this didn’t break them they took away the light that streamed through the window. They took away the space under the door. They took away the sound of music, poetry, books and literature, photographs of loved ones, letters home, their visits.

They broke their fingers. They smashed their teeth. They broke their noses. They burst their eardrums. They blacked their eyes. They poked grubby fingers into their bodies. They plunged them into cold baths and forcibly sheared them. They beat and batoned them during wing searches and wing shifts. They insulted them, berated them, abused them, cursed them.

And still they couldn’t get Martin Hurson to say, ‘Sir’.

They took away everything leaving them with nothing.

Or so they thought.

What sons, what brothers, what noble soldiers this nationalist community gave birth to. One hundred years ago we were deserted by the South and left on our own. We were isolated. They tramped us down into the ground. But where was the victory for unionists and the British state? Their policies are in tatters. They run around headless.

Our community, an artificial minority in a sectarian state, when we used to be the majority in our own island, produced sons like Martin Hurson. This small place of the Six Counties produced ten hunger strikers—and a long list of volunteers ready to take their place.

It cuts our breath. It stops our hearts, the greatness of Martin, his sacrifice, the power of his conviction to starve day after day, to resist the natural desire for life-giving nourishment. How did he do it, how did he keep going over those weeks in July until his early death at the age of 24?

He was fuelled by his love of Tyrone, its people and the people of Ireland, the belief that we have the right to be free without English or British interference and will assert that right despite the forbidding cost to our personal fate.

Martin and his comrades and the nationalist community of the North during this struggle became nothing less than the conscience of Ireland as a people. Partition, one hundred years ago, certainly punished us in the north. We were its chief victims. But in the South partition also undermined the national spirit, damaged the national psyche—the creation of Free Statism almost smothering the aspiration for independence that had been inspired by Easter 1916.

1981 changed everything. It is one of the most seismic moments in the history of twentieth century Ireland. The sacrifices of the ten men translated into support for a reinvigorated struggle—on all fronts.

In 1981 I came up the same road I travelled today, to Augnnaskea. I came to see John Hurson to let him know that his son Martin was joining the hunger strike but Martin had already told the family. On Sunday, 5th July, when we were hoping that negotiations would lead to a breakthrough, I visited the hunger strikers in the prison hospital. But Martin was too ill to attend that meeting. On my left was Joe McDonnell in a wheelchair who had three days left to live. Beside Joe was Mickey Devine who would die on August 20th. Across the table was Kevin Lynch, Thomas McElwee, and Kieran Doherty who had been a year below me at school. All were destined to die in the days ahead.

It was a harrowing scene and one I shall never forget. Their dignity, their determination, their bravery was humbling. The British government, of course, had been toying with them, teasing and tempting them in the hope that it could break the hunger strike.

Although, as I said, I had never met Martin I feel I got to know the calibre of the man, the family into which he was born and grew up, the tribulations he faced.

In 1982 I ended up being elected for Sinn Féin for Mid-Ulster to the Assembly, and between 1982 and 1986 my second home was that of Martin’s brother Francie and his wife Sally who were the best hosts of any house I have ever stayed in.

Although I’d been in jail with Tyrone men when I was interned, I had no idea what it was actually like to live in the rural countryside. I am from West Belfast and there is a certain amount of protection in large numbers. If you were stopped by the Brits and the RUC on the Falls Road there were dozens of witnesses—which is why the Brits preferred to do a lot of their killing in the dark of night. But driving through country roads was scary. Camouflaged Brits could jump out at any moment. They could assault you. They’d later deny they had even been there.

Worse was the UDR—the former B Specials—at night. They often physically beat up young men going to or coming from dances. They needed no excuse to abuse their neighbours. In Belfast if your house was being raided in the early hours, again you had the support of your neighbours but in the countryside you could be completely isolated, which only added to the terror.

The state, the British, colluded with loyalists in their dirty war. Armed them, gave them information which led to the killing of the four lads at O’Boyle’s pub in Cappagh, killing Tommy Casey at Kildress, killing pregnant Kathleen O’Hagan in Greencastle, a mother of five.

And yet the nationalist people and the IRA triumphed over the might of the Brits.

I was in jail when the ceasefire was called. I remember reading reports that the British army was admitting that there was a military stalemate. James Glover, former General Officer Commanding the British Army in the North, said: ‘In no way, can or will the Provisional Irish Republican Army ever be defeated militarily.’ In 1992, a senior British Army officer in The Times newspaper went further: ‘the IRA is … better equipped, better resourced, better led, bolder and more secure against our penetration than at any time before. They are an absolutely formidable enemy. The essential attributes of their leaders are better than ever before. Some of their operations are brilliant…’ In July 2007, the BBC published an internal British Army document in which one military expert said that it had failed to defeat the IRA. It described the IRA as ‘a professional, dedicated, highly skilled and resilient force’.

As in one’s passage through life, there is no blueprint for any independence struggle, which shows you a clearly set out path from A to Z. Unforeseen obstacles will appear. Unforeseen opportunities will arise. Contingencies will have to be adapted. More circuitous routes might have to be taken towards you goal.

But the republican struggle is renowned for its ingenuity. Where there is a problem there is a way. In prison, republicans went under the wall, went through the wall, went over the wall, went around the wall, to achieve their objective.

From 1968 we rose up, we defended ourselves, we fought our corner literally at our corner, or on our country lanes and roads. We represented ourselves. We garnered popular support and changed public opinion and radically changed the political landscape.

But it didn’t end with the ceasefire, with the early release of the prisoners, with the Good Friday Agreement or any of the other pledges from the British. The struggle goes on. Unionists, who used to march on the Falls Road on the Twelfth when I was young, are having a problem adjusting to the new realities. They complain that they are second class and that the nationalists are getting everything—which is untrue. We are merely taking back what was once denied us.

The struggle goes on and much more is needed to be done.

There will be no true peace and no true justice and no true freedom until Britain’s interference in our affairs is finished for good.

I want young people to remember what it was like before. These roads round which swanned the British Army, the UDR and RUC trying unsuccessfully to stamp their authority. I want young people to remember the bad, ‘good old days’. The raids, arrests, the torture in interrogation centres. Remember what Martin Hurson and our people suffered and endured.

Treasure the freedoms you have.

Enjoy the sound of peace in a state that was built on the agonising cries and tears of your parents and grandparents.

If you listen closely to the sound of peace you will also hear the sound of a state creaking under the pressure of a proud, risen nationalist people. What you will hear is the sound of this state breaking down under its contradictions.

What you will hear is the sound of freedom, of independence, is the sound of Ireland finding its voice thanks to the republican people of Tyrone, thanks to 1981, thanks to ten young men who defeated the British—thanks to Martin Hurson.