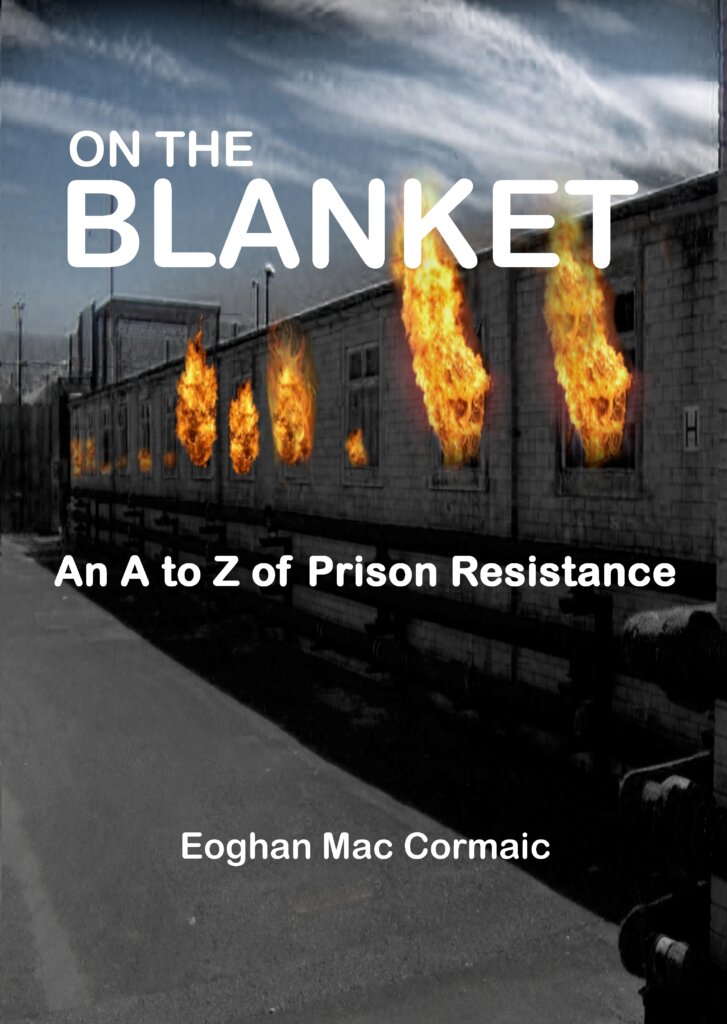

Many republican memoirs have been published in recent years covering a variety of prison experiences, from Síle Darragh’s John Lennon Is Dead, to Jaz McCann’s 6000 Days. Eoghan ‘Gino’ Mac Cormaic, who was sentenced to life imprisonment, first published his book as Gaeilge with the title, PLUID – Scéal na mBlocanna H. It has now been translated into English with additional material. Here, Jim Gibney, who was on the National H-Block/Armagh Committee in the early 1980s reviews On The Blanket – An A to Z of Prison Resistance.

-oo0oo-

My abiding memory from jail of Gino Mac Cormaic is of a young Alexander Solzhenitsyn-like figure in his cell, sitting at a desk, his light frame slightly bent forward, a rolled, smouldering cigarette hanging from his mouth, his head buried in a jotter, pen in hand.

It was my third time in jail. I think it was 1984 in the H-Blocks, after the restoration of political status following the 1981 hunger strike. I hadn’t long been sentenced. Before that, the last time I had spoken with Gino was in Crumlin Road prison in 1977 when we were both on remand, although I won my case and was released.

Gino was sentenced to life imprisonment and had been through almost five years on the blanket protest. He had suffered brutal beatings during wing searches and wing shifts but had always remained philosophical.

The Solzhenitsyn comparison arose from his likeness to the dissident Russian writer from a photograph taken in a Soviet Union gulag.

Two of our conversations stick out: Gino’s passionate desire to have a family, should he ever get out of jail (which he fulfilled with distinction, married now with three children); and his aim to produce a dictionary of all the Celtic languages still in use in Europe.

Given the circumstances we were both in it was the production of the dictionary that took up most of the conversation. Words were important to Gino (he’s a real wordsmith) and so I was not surprised with the publication of his prison memoir, as Gaeilge, first as PLUID – Scéal na mBlocanna H, and now in English, On the Blanket: An A to Z of Prison Resistance.

It is witty, moving, provocative, passionate and leavened with the black humour that saw the blanket men and the women in Armagh through those black days and nights.

A sample of some of the words conveys the book’s heroic story of daily resistance by over 400 prisoners.

Agóid replaced the word ‘protest’ because it didn’t convey enough what ‘agoid’ entailed – the blanket, the no-wash, no slop-out and the mind-numbing violence of prison warders – ‘to be ar an agóid was to be unbroken.’

Aire had many meanings: attention, watch out, danger’s about; Aire! Paráid ar Aire (Attention! Come to attention) from their OC, invisible behind a cell door somewhere along the wing.

‘Even in the isolation of a prison cell, even in a cell stripped of everything, even stripped of our own clothes, standing wrapped in a blanket, barefoot, sometimes terrified and oftentimes troubled we were part of an army. We were volunteers and we were undefeated’.

Three random words from the book display Gino’s love of words – ciborium, the small silver chalice which held unconsecrated hosts, used during aifreann (mass,) and thole – a Scottish word that Gino used to describe the impact of Joe McDonnell’s death on the lads in the wing he was with since 1977, and psephology, which he got from Michael Culbert, ‘Tic Tac’, or more accurately from his wife Monica who smuggled in a cutting from the Readers’ Digest. Psephology is the statistical study of elections.

Achs were priceless cigarette butts which the lads deftly picked up with the toes of their bare feet unnoticed by the ever-vigilant warders. Ach in Irish means but, and in the jailtacht it was lost in translation and adapted to mean the fag end of a cigarette!

The Bean Uasal (literally, ‘lady’) was the highly regarded and trusted link between the prisoners (taobh istigh) and the leadership outside (taobh amuigh). It was Maire Moore’s code name. She led a team of indefatigable women who braved the harassment and hassle of the prison warders to smuggle much-needed comms into and out of the H-Blocks to the co-ordinator of a complex, clandestine and very effective system of contact who used the codename Liam Og, which was Tom Hartley.

Gino was in charge of the Rud Eile (the other thing), a code name for the secret crystal-set radio, he carried inside his body.

The contraband crystal set radio on which the blanket men received the news of Bobby Sands’ election victory in Fermanagh and South Tyrone

It was through the earpiece of the Rud Eile that he heard and then relayed to his comrades the result of Bobby Sands winning the Fermanagh and South Tyrone. ‘Bua ag Bobby!’ Bobby has won – followed by an instantaneous explosion of cheering, crying, banging, whooping. And hoping.

‘Elation, joy, sadness. A feeling never to be repeated, a day never to be forgotten. Bobby Sands MP!’

Gaeilge was spoken and taught not of boredom but out of culture and tradition. Republicans in jail in every generation had learned and taught Irish.

The lexicon was familiar: ranganna Gaeilge, Irish classes; múinteoirí – teachers; daltai – students; scrúdaithe – exams. The goal to achieve An Fáinne Glas (green); An Fáinne Airgid (silver) or An Fáinne Ór (gold), and to speak liofa (fluently) on the wings.

Over the years I’ve read and reviewed a number of books and no matter how often you read about prison brutality it still impacts emotionally.

Even though Gino is writing of events from forty years ago it doesn’t quell the anger. The people who beat and humiliated these prisoners largely got away with it. Reading of his account of being forcibly washed by several screws while he was naked, separated and isolated still makes one’s blood boil.

It is the humour of the prisoners, their lightness of being, that ensures they rise above the squalor, the sectarian violence, through singing, through slagging each other, through comforting each other. The story about one Danny Aiken is hilarious but you’ll have to get the book to read it.

There is a powerful piece of writing, which I’d like to quote in full before I finish. And it explains the endurance of the blanket protest, solitary confinement, beatings, the seven-month long 1981 hunger strike. And it is called Comradeship:

Comradeship. It was the oil that kept the wheels of the protest turning day after day, week after week, year after year. It was all around us, steering us, strengthening us. It was often un-named and undefined, like something so big that at any given time we could only see or feel part of it. It was so tiny it was the word of support down at the pipe or at the window. It was so huge that it was an elephant being described by a blind man. It was easier to define by what it caused men to do than by trying to describe it in totality.

Comradeship was the bond that tied us together. Outside prison walls comradeship might mean the heroism that would see someone risking their own life or freedom to assist a comrade in trouble, or to share the burden being carried by a comrade. Comradeship in those circumstances was almost physical. In the H-Blocks, however, comradeship was subtler. It was all about the common experience, the common support for each other, and that was no easy ask.

In normal circumstances when you see or hear someone in trouble the instinct is to reach out, to help, to share the load. In the H-Blocks the most difficult part was the inability to reach out or to help. The steel doors trapped us from rushing to the assistance of a comrade being beaten and indeed the true challenge was to listen to the plight of a friend neighbour or comrade being dragged and kicked and batoned by screws, torn apart by knowing that the only help you could offer was to endure the same level of beating minutes later while he, in turn, listened helplessly. It was a gut-wrenching feeling, and it remains a gut-wrenching memory.

Comradeship was the ability – the duty – to offer words of support without pity, to offer rage without action, to offer hope without promise. Comradeship was far, far more than sharing the last shreds of tobacco, or scraps of food; it was more than smuggling comms in or out for a wing- or cell-mate. It sometimes required the need to suppress the impulse to rage and attack when a comrade was being hurt by the system, and sometimes to talk – and listen – late into the night with patience and understanding to some comrade’s pain. And keeping them strong.

It meant standing firm just as your comrades were standing firm; rising each morning to face the certain uncertainty of each new day in the same way your comrades were rising to face the same. It meant rebuilding morale that had been broken, and allowing, too, your own damaged morale to be rebuilt. It meant doing first and questioning later, accepting new challenges and not leaving the task to others. It meant having a thick skin and no pretensions but simultaneously an inner pride that proclaimed that you would not be broken. It meant the art of detaching from what was all around and reminding yourself that all is relative, all is temporary. There will be good days for all the bad.

It meant blocking out thoughts that brought sentiment. Hardening the heart to another life, caring more for comrades beside you, than for anyone. For some among us it meant, eventually, giving everything they had, their lives, for the wellbeing of others.

That was comradeship.

On The Blanket is available from the Sinn Féin Shop, Dublin, €15.00; and from An Fhuiseog, Falls Road, Belfast, for £13.

-oo0oo-