Responding to a comment from a Conservative MP, calling for Irish prisoners in British jails to be transferred back to Ireland, Danny Morrison, recalls how throughout the conflict the British government adopted the opposite stance and cruelly refused to repatriate Irish prisoners. His article was published in the 6th December edition of the Andersonstown News.

The story was on page nine of my newspaper. It wasn’t a huge story yet the headline which contained the words ‘prisoner transfer’ viscerally threw up a lot of emotion and anger about the way things had been and need not have been.

The headline was based on a crass comment from an English Tory – ‘MP links prisoner transfer to British loan for Ireland’.

Last Thursday, it was reported, that as a cost-cutting measure the British government wants to close six jails and move a number of Irish prisoners to prisons in the Irish Republic to finish their terms. There are up to 1,000 and many of them are actually long domiciled in Britain with wives and children.

MP Philip Hollobone – a surname suggestive of spinelessness – couldn’t help but quip that “given that we are about to lend them more than £7 billion, could the Irish Republic be persuaded to pay for the incarceration of these people by taking them back to jails in their own country?”

For almost thirty years there has been a European ‘Convention on the Transfer of Sentenced Persons’ but long before that many states operated a policy of transfers of foreign nationals, and states within their own boundaries regularly moved sentenced prisoners to jails closer to home both as an act of humanity and because it made for a more contented prisoner population.

Unless, of course, you were Britain and your prisoners were Irish republicans.

Or, you are Spain and your prisoners are Basque separatists whom you have incarcerated a thousand, punitive miles from home.

During our conflict the traffic was all one-way, the British-way. British soldiers, when rarely convicted of murder or rape or assault or robbery, were automatically transferred to prisons in Britain for “the sake of their family and their own security”, to quote a former secretary of state.

Thus it was that two years after being convicted of the murder of Thomas ‘Kidso’ Reilly on the Springfield Road in 1983, Private Ian Thain was released from an English jail on licence and was allowed back into his regiment.

Thus it was that Private Lee Clegg, who killed two teenage joy riders in 1990, but was sentenced for just one killing, that of Karen Reilly, was transferred to England to serve a mere four years before being released, and was allowed not just back into the British army but was promoted.

Thus it was that Scots Guards Mark Fisher and James Wright, sentenced to life for the killing of 18-year-old Peter McBride in the New Lodge in 1992, and after serving only six years, were released in 1998 by Mo Mowlam and reinstated in their regiments. They were preferentially freed prior to the introduction of the Early Release Scheme negotiated in the run-up to the Belfast Agreement and consequently the conditions of ‘released under licence’ did not apply to them.

Now, compare this to the treatment of Irish republican prisoners.

After their arrests in London on IRA-related charges and being sentenced to life imprisonment in 1973, the sisters Dolores and Marion Price, Gerry Kelly (now an MLA) and Hugh Feeney were refused repatriation to jails in the North. They went on hunger strike and were brutally force-fed for two hundred and six days.

Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg, IRA Volunteers convicted in Britain, had also requested repatriation and went on hunger strike, Michael being force-fed for the last time on the evening of June 2nd, twenty four hours before his death after sixty-four days without food.

In an earlier hunger strike lasting seventy days, a severely debilitated Frank Stagg agreed to end his protest after assurances from the prison authorities that a ‘reasonable’ date would be set for his transfer to a prison in Ireland. When the British reneged Frank went back on hunger strike and died in February 1976.

There are many, many sad stories about the conflict. Jail was tough here, particularly during the blanket protest and hunger strikes, but there was strength in numbers and comfort in the knowledge that the IRA was not far away.

Those in England had less such solace.

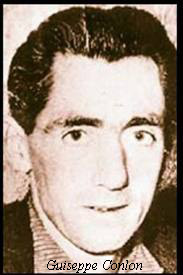

There, Irish prisoners were subjected to racism and persecution. You only have to read the accounts by Paul Hill, Gerry Conlon and the Birmingham Six, and how they strove to survive, to realise how severe it was even for those who were not in the IRA and lacked organisation, muscle and cohesion. Gerry Conlon’s father Giuseppe travelled from Belfast to visit his son, only to be arrested, charged, falsely convicted and died in prison still protesting his innocence.

Families of republican prisoners would make long, long journeys to faraway jails only to be told at the prison gate that their son or daughter or husband had been transferred the night before to a new prison, hundreds of miles away. ‘Ghosted’ was the apt description the prisoners and their families came only too well to recognise.

Oh but could we ghost the British presence and interference in Ireland!

“Given that we are about to lend them more than £7 billion, could the Irish Republic be persuaded to pay for the incarceration of these people by taking them back to jails in their own country?”

Mr Hollobone, you fool, you could never in eight hundred years repay the drain that Britain has been on Ireland’s natural resources, its people, their happiness, their contentment, their prosperity, the lives of her sons and daughters…