The depiction of a meeting between poet and Nobel Literature Laureate Seamus Heaney and Danny Morrison prior to the 1981 hunger strike has been disputed by the former Sinn Fein Director of Publicity.

The depiction of a meeting between poet and Nobel Literature Laureate Seamus Heaney and Danny Morrison prior to the 1981 hunger strike has been disputed by the former Sinn Fein Director of Publicity.

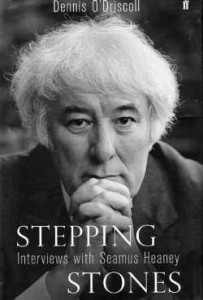

Recently, a new book, ‘Stepping Stones – Interviews with Seamus Heaney’ by Dennis O’Driscoll , was published in which Heaney speaks about his reaction to the situation in the northern jails. Bobby Sands had famously written about poets:

The poet’s word is sweet as bird,

Romantic tale and prose.

Of stars above and gentle love

And fragrant breeze that blows.

But write they not a single jot

Of beauty tortured sore.

Don’t wonder why such men can lie,

For poets are no more.

In the book Seamus Heaney is reminiscing about old train journeys when he is asked a question by O’Driscoll: Another memorable journey, clearly, was the one you memorialized in ‘The Flight Path’, where you’re hectored by the Republican spokesperson about not writing something for the Republican cause. The poem is stated to be ‘for the record’, so I assume you described the encounter as it happened.

Heaney replies: “The account of what went on in the train is as it happened, yes. I make the speaker a bit more aggressive than he was at the time, but the presumption of entitlement on his part, which was the main and amazing aspect of that meeting, is rendered faithfully.

How public was the confrontation?

“It was all done pretty discreetly, actually. My interlocutor was the Sinn Fein spokesman, Danny Morrison, whom I didn’t particularly know at the time. He came down from his place in the carriage and sat into the seat in front of me for maybe eight or ten minutes. There was nothing loud or noticeable about it; it was as if two people who discovered themselves on the same train by coincidence were getting reacquainted. I didn’t feel menaced. It was a straightforward fact-to-face test of will or steadiness. I simply rebelled at being commanded. If anybody was going to pull rank, it wasn’t going to be a party spokesman. This was in pre-hunger-strike times, during ‘the dirty protest’ by Republican prisoners in the H-Blocks. The whole business was weighing on me greatly already and I had toyed with the idea of dedicating the Ugolino translation to the prisoners. But our friend’s intervention put paid to any such gesture. After that, I wouldn’t give and wasn’t so much free to refuse as unfree to accept.”

Danny Morrison contradicts this version of their meeting.

“If Seamus wrote a contemporaneous account of what happened, for example, a diary entry, and is quoting from this and not memory then I will bow to his opinion. However, in a letter published about fifteen years ago in a newspaper, I think I am right in saying that he at first said it was Kieran Nugent [the first blanket man] who had approached him. My recollection of our meeting is different. In 1979 and 1980 I had approached many people in public life to ask them to make some kind of statement objecting to the treatment of the blanket men and the women in Armagh Prison. For example, I saw Douglas Gageby, the late editor of the ‘Irish Times’, in Dublin Airport as both of us were returning from abroad and I lobbied him. He agreed to meet up and I had a meeting with him in Westmoreland Street which resulted in Gageby writing an editorial in the paper.

“I saw Seamus Heaney sitting two seats down across the carriage from where I was. I went over and asked if he minded me sitting down and talking to him. He was very polite. Back then I would not have had the media profile I later had so I explained who I was. I told him about the dire situation in the jails and the fact that the prisoners were talking about going on hunger strike. I asked him to consider if there was anything he could do on their behalf, if he could add his voice to the growing complaints. For example, Archbishop O Fiaich had, by this time, visited the H-Blocks and, to the embarrassment of the British government, had compared the prison to the sewers of Calcutta.

“Seamus told me he was writing a poem and had been thinking about the prisoners. He told me the story from Dante’s Inferno of Count Ugolino who was imprisoned with his children and grandchildren underground and left to starve, Ugolino’s eating his dead children’s flesh to delay his own starvation. Seamus said he imagined that this could be some sort of metaphor for hunger striking though I was lost as to what he meant.

“In ‘Stepping Stones’ he says that he felt he was being ‘commanded’ and for that reason changed his mind and didn’t dedicate his Ugolino translation to the prisoners. I find that explanation hard to reconcile with the fact that after our conversation we parted with a handshake, he gave me his address and telephone number and agreed to read the poetry of Bobby Sands [which included criticism of artists and poets for their silence in the face of oppression] and which Sinn Fein was later to publish as the pamphlet ‘Prison Poems’. I sent him the poems and he brought them back to the Sinn Fein offices in Parnell Square, Dublin, a week or two later and left a message for me in which he said that the H-Block Trilogy read like or was derivative of Wilde’s ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’ [which, of course, its metre was based on].

“And that was the extent of our contact. The collection he had been working on was later published as ‘Station Island’ and in the eponymous poem he refers to Ugolino and, indeed, there is a reference to Francis Hughes. I mention ‘Station Island’ in my introduction to the essays on the Hunger Strike the Bobby Sands Trust published in 2006.

“Apparently, given that the poem ‘The Flight Path’ was not published until 1996 in the collection ‘The Spirit Level’, it was sixteen years after our discussion before Seamus creatively reacted and in a way, given his explanation and claims in ‘Stepping Stones’, that I feel has distorted and exaggerated the nature of our exchange.”

In ‘Stepping Stones’ Seamus Heaney elaborates further on 1981. O’Driscoll says: During the H-Block hunger strikes, it must have been impossible not to feel something like guilt at not being able to help alleviate the situation or contribute to its resolution.

“It was impossible, yes. This was during the time when ‘Station Island’ was being written, and the self-accusation of those days is everywhere in the sequence. Also in individual poems such as ‘Chekhov on Sakhalin’ and ‘Sandstone Keepsake’ and ‘Away From It All’. Because of my earlier brush with Mr Morrison on the train, during ‘the dirty protests’, I was highly aware of the propaganda aspect of the hunger strike and cautious about being enlisted. There was realpolitik at work; but, at the same time, you knew you were witnessing something like a sacred drama. If I had followed the logic of the Chekhov poem, I’d have gone to the prison, seen what was happening to the people on the hunger strike and written an account of it, ‘not tract, not thesis’. In truth, I was ‘away from it all’ during those months: at a physical remove, living in Dublin, going on holiday in France.

In ‘Frontiers of Writing’, you touch on the evening when the body of Francis Hughes – a neighbour’s son and the second hunger striker to die – was being waked in his home in County Derry. You were not only in Oxford when he died, but staying – of all places – in a British cabinet minister’s rooms.

“It was bewildering. Charles Monteith had brought me as his guest to that year’s Chiceley dinner in All Souls College. The Fellow’s room I was assigned for the night was one that belonged to Sir Keith Joseph, the then Minister of Education in the Thatcher government. It took me ten years to come back to that occasion and see it as emblematic of the general stalemate. Francis Hughes was a neighbour’s child, yes, but he was also a hit man and his Protestant neighbours would have considered him involved in something like a war of genocide against them rather than a war of liberation against the occupying forces of the crown. At that stage, the IRA’s self-image as liberators didn’t work much magic with me. But neither did the too-brutal simplicity of Margaret Thatcher’s ‘A crime is a crime is a crime. It is not political.’ My own mantra in those days was the remark by Milosz that I quote in ‘Away From It All’; ‘I was stretched between contemplation of a motionless point and the command to participate actively in history.’

Whatever your proper doubts about the ‘propaganda aspect’ of the hunger strikes, had you some sympathy for the men, even some admiration for their courage?

“Of course I had. That was part of the cruelty of the predicament. At the same time, I was wary of ennobling their sacrifice beyond its specific history and political context. Uneasy, for example, about seeing it in the light of Yeats’s The King’s Threshold, his play about a hunger strike in the heroic age, in the other country of the legendary past. Anthropology didn’t get you out of the moral corner you were backed into. One thing that had some point, if not great resolution to it, was when I attended the wake of Thomas McElwee, the eighth man to die. He was a cousin of Francis Hughes and lived adjacent. It happened that I was up in County Derry when his remains were returned to his home. I remember the sunny August afternoon when I walked across their yard, into the room where the corpse was laid out. The usual ritual of paying last respects. It gave some relief, to me at least. The family would have known that I wasn’t an IRA supporter but they would also have known that this crossing of their threshold was above or beyond the politics that were distressing everybody.

Did they, or the Hughes family, seek your intervention or intercession?

“Never. By that time, I’d been away from the Bellaghy area for twenty years and probably didn’t figure much in their minds as a local who could be appealed to.”

Did literary friends like Seamus Deane and the Australian poet Vincent Buckley encourage an overt pro-hunger-strike stance?

“I don’t recall being pressed by them to change my ways but equally they left me in no doubt that they took a different view. I realized that Vincent Buckley had an unflinching loyalty to the hunger strikers when he began a sequence of poems about them, even naming them individually. As far as I was concerned, Vincent was romanticizing the situation that pertained by then. He was caught in a time loop and was holding on to a late-1960s, early-1970s vision of ‘the struggle’. He’d been involved early on in Australia, I think, in fundraising for the internees’ families, and had retained contacts with various Republican sympathizers in Ireland. I don’t mean IRA volunteers, although Vincent was closer to being a political activist than I could ever have been.”

‘Stepping Stones – Interviews with Seamus Heaney’ is published by Faber and Faber Ltd at £22.50 and can be ordered through Amazon

For reviews of ‘Stepping Stones’ see the Sunday Observer ; the Daily Telegraph ; the Scotsman and the Times