The comms of Bobby Sands and others, smuggled out of the H-Blocks of Long Kesh, particularly during the hunger strike, are now world famous, writes Gerry O’Hare.

Far less well-known is that a republican prisoner, as long ago as the 1950s, had written a prison diary, entirely in Irish, which had also been smuggled out – this time from Belfast’s Crumlin Road Jail. Here, Gerry O’Hare reviews a book based on these diaries.

Eamon Boyce’s diary, written when he was incarcerated during the IRA’s 1956-62 ‘Operation Harvest’, has now been translated and edited by academic Anna Bryson – and belatedly published under the title, ‘The Insider’.

But better late than never …

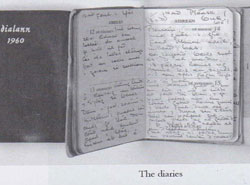

Boyce’s story of daily life in The Crum’ was originally written into small diaries that inexplicably ‘by-passed’ the jail censor over many years. Always fearing the risk of discovery by the authorities, his story, as told, is remarkable. He even managed to keep his diaries secret from most of his comrades and fellow prisoners.

Anna Bryson, who edited the book, is the holder of a Ph.D. in History from Trinity College, Dublin, and was also lead researcher for Professor Sean McConville’s monumental volumes on Irish political prisoners. (The volume, 1848-1922, running to 820 pages is currently available.) McConville is a professor in the Department of Law, Queen Mary, University of London. Bryson was interviewing the former republican prisoner for McConville’s project when he unexpectedly presented Bryson with his own remarkable diaries and, with the assistance of Kathleen Rigney, they have been faithfully translated from their original Irish.

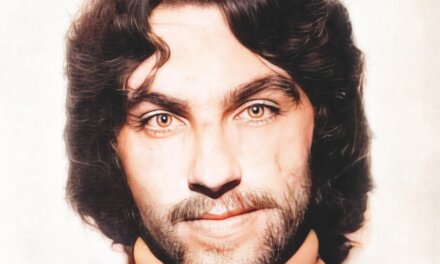

Boyce learned all his Irish whilst in prison. A Dublin-based CIE bus driver, he was the leader of a 1954 IRA attack on Omagh barracks for which he was sentenced to twelve years for Treason Felony on three counts at the Belfast Winter Assizes.

‘Operation Harvest’ had not started at the time of his imprisonment but began and continued while he was in jail. The book relates Boyce’s frustrations with that ultimately unsuccessful campaign as well as daily life behind prison bars, friendships, inevitable fall-outs, internal politics and eventual freedom in 1962.

It all began when, sitting in his cell at Christmas 1956, he received a parcel including a Gael Linn small diary which the censor had missed. Inspired by that good fortune, he began to plot how he could smuggle material out of the jail. One method was by stuffing written pages into the hollow interiors of crosses, made from matchsticks. Another five diaries were smuggled in for him and he began to fill their pages before they were duly smuggled out again. It was Boyce’s way of ‘doing

Time’.

He also managed to smuggle in a small radio (another precursor to the later exploits in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh during the blanket protest).

And so we come to the content of these remarkable journals. But first, a note about the book as printed. It includes a detailed annotation, notes and index putting Boyce’s diary entries and comments into the context of the time including names, events and political goings-on outside the prison. The index is a book in itself and this reviewer, after some time, decided to begin by focusing, first, on the narrative given in Boyce’s own words before re-reading the book to take in the context. The index is so detailed that it is, without doubt, one of the best I have ever come across.

The diaries are, at times, depressing and at others’ joyous as he relates the daily life he faced over his years in jail. The names flow by of past volunteers, sadly now mostly no longer with us. They include both sentenced prisoners and internees between 1956-62.

Petty incidents became huge crises for Boyce as he tried to make life as bearable as the harsh regime that existed in Crumlin Road Jail at that period would allow.

As a former Crumlin Road inhabitant, I – and others of my generation – cannot begin to realise how hard time was served back then. We had it bad, but it was infinitely worse in the 1950s.

As a former Crumlin Road inhabitant, I – and others of my generation – cannot begin to realise how hard time was served back then. We had it bad, but it was infinitely worse in the 1950s.

Visits are highlighted, particular those with his mother and his brother, Sean. An example: “Saturday 5th April 1958: My mother and Sean up. She looks well enough but she has been ill. I had a short visit and I got a great Easter parcel. Mam says she’ll visit Charlie Murphy in a while.”

Visits were severely restricted and at the whim of a screw could be terminated for the simplest of petty reasons.

Boyce’s writings are geared towards his release and his frustration shows as other members on the Omagh raid are all released ahead of him. He watches with frustration the failure of the IRA campaign to make much headway. He is both delighted and disappointed at different times

with the success and failure of Sinn Fein candidates. Another example, an entry dated Friday 9th October, 1959: “Awful result in the election – Sinn Fein destroyed altogether – I can’t talk about it. A nice letter from Johnny and Florrie. They were delighted with the music box.”

The refusal of chaplains to administer the sacraments at Mass pained him. The bishops of the time decreed that those involved in the IRA were to be refused the sacraments. The Prison Chaplin then was Fr. Paddy McAllister (who later taught me when I was a pupil at St Malachy’s College, next

door to Crumlin Road Jail). He forgives Fr. Paddy, though, as he states, the priest was dictated to by the bishops.

On a happier note, a friendlier chaplain ignored the bishops’ diktats and gave absolution to any prisoner who wished it.

Escape plans are a thorny issue with Boyce as they usually brought down severe searches (and posed the danger of exposure to his diaries). In December 1960 Danny Donnelly escapes. On 2nd January, Boyce writes in his diary: “The searches are going on. I’m afraid that I’ll lose these diaries. I had to go to bed at eight o’clock with the cold. The English princess (Margaret) is in the Free State”.

As his time of release comes nearer, his frustrations mount. And his final diary note leaves one sharing his unhappiness.

Tuesday 18th September 1962: “A letter today. Thank God. My mother, Sean and Fr Livinus all right, but they are fed up waiting for me. Pearse (Doyle) is in Mungret College. Donal (Murphy) will be home on 2.10.62. but there’s no word of Joseph Doyle…

“This is the last part of my diary after seven years writing. With God’s help, there will be nothing important to write between this and freedom. I’m grateful to God that everything was okay from the day I came in here.

“Of course, I’m very disappointed about political maters. I was full of hope coming in, but now I don’t suppose that there’s any solution to the republican question. It’s too late, but we had our chance.

“It’s a pity that South, and the other men, died – as there won’t be any result from their sacrifice – but that’s life. I pray that God will give me luck and blessings in the life that is ahead of me”.

Finally in a ‘Question & Answer’ interview with the editor/author, he is asked was his jail life a worthwhile experience? His answer speaks volumes:

“In many ways yes. I kept my self respect and the people I met – mostly men – during the whole course of my involvement with the movement, it’s been privilege to know them and I’ve been a better person because of them. Now if I say that to somebody up north, they might laugh – but I would definitely say that”.

‘The Insider – The Prison Diaries of Eamonn Boyce 1956 – 1962’, edited by Anna Bryson. Published by the Lilliput Press, Dublin, 62-63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill, Dublin 7. Price €40