Former republican prisoner Gerry O’Hare reviews the monumental study on Irish political prisoners (1848-1922) by Professor Sean McConville which covers the period of the imprisonment of O’Donovan Rossa, Tom Clarke and Roger Casement. McConville shows how punishment came to shape the nationalist consciousness and the part it played in the development of Anglo-Irish relations and the birth of the Free State/Republic of Ireland.

The Untameables – Gerry O’Hare

There has been a proliferation of books in recent time about prisoners and jails. Some of the authors are ex-prisoners which lends a certain credibility to their accounts. This book, however, is by an academic.

Professor Sean McConville, who works at the Department of Law, Queen Mary College, University of London, has produced a tome of over 800 pages dating from the ‘Young Irelanders’ to the War of Independence in 1922.

Such an effort, this reviewer felt, deserved more than a fleeting read, so time was set aside to give the author, and his work, due credit.

Firstly, who is the author? McConville is a Professor of Criminal Justice and Professorial Research Fellow. He has published widely on imprisonment and related political and legal issues, including work on Britain, Europe and the United States. He also encouraged Anna Bryson to edit and publish ‘The Insider’, the story of Eamon Boyce’s diaries in Crumlin Road Jail, 1956-1962 (reviewed here).

In an introduction, McConville tells us modern Irish nationalism took form in the years 1848-1922. Campaigns ranged from the ballot box, civil disobedience and conspiracy, to ‘terrorism’, insurrection and guerilla war.

While the punishment of ‘offenders’ presented successive governments with seemingly intractable problems, imprisoned revolutionaries discovered and exploited numerous opportunities to continue and intensify their struggles. The details of their stories makes this book probably the most comprehensive and detailed study yet of the political use of imprisonment in these years.

Drawing extensively on archives and special collections in Ireland, England, the USA and Australia, many hitherto unused, McConville shows how punishment came to shape the nationalist consciousness.

Accounts of prisoners’ experiences and official reactions are given context by matching chapters, each describing the political and organisational components of successive phases in the nationalist and republican struggle. Successive governments’ responses were conditioned by legal and constitutional factors as well as attitudes and opinions in Britain, Ireland, the USA and Australia. Through considering these, as well as British and Irish party politics, McConville tries to tell the full story of the part played by political imprisonment in the development of Anglo-Irish relations and the birth of the Irish State.

The main story is told with extensive references on each page. This reviewer eventually discovered that it was easier to read the narrative – and then to go back for a second read, using the references.

The book is broken down into sections and each could have made a book in itself.

One section that I found fascinating and distressing was that which covered those who became known as the ‘Dynamitards’. It covers a shocking period, when explosives were first used in a campaign which ended in abject failure.

In 1867, Alfred Nobel had managed to stabilise the powerful and extremely dangerous explosive, nitroglycerine, in such a fashion that it could be manufactured commercially – that is, made into dynamite.

We had read earlier that Fenianism, both in Ireland and America, was at a low ebb when in 1870 Gladstone released the Fenian leaders who were exiled to America. But there were many factions and the Fenian leaders, we learn, failed to unite the Irish in America. It was about this time that Clan na Gael came to the fore.

The Clan recognised the authority of the Irish Republican Brotherhood which was based in Ireland and Britain. It had secured its place in the leadership of militant Irish-Americans in 1876 when it brought off the rescue of six Fenians in jail in Western Australia, an operation organised by John Devoy and executed by John J. Breslin. The escape captured the admiration of Irish people at home and abroad and whetted the idea among the most militant that an operation successfully carried out half way round the world could now be replicated closer to home – in England.

But internal politics and personality problems meant it was three years before the team of volunteers actually made it to the shores of England. The campaign was a disaster and many of the team were captured and sentenced to life imprisonment. Among the prisoners was Thomas Clarke, who survived his sentence despite unbelievable treatment, whilst most of his colleagues died or went mad.

Many debates took place in the British parliament to seek amnesty before the prisoners were eventually released. The men were isolated in England and suffered the worst degradation from their jailers who we learn were ex-sailors and former British soldiers who took sadistic pleasure, approved by the governors, to break the Irish lifers.

‘Life’ in those days meant twenty years. Relatives and friends at home in Ireland only learnt of their conditions through rumour. The prisoners had to wear soiled clothes, taken from ordinary criminals. If they complained they were forced to take a cold bath and wash the dirty clothes at the same time.

Their conditions and treatment would make your blood boil.

If Clarke managed to keep his sanity by being determined to beat the system what are we to make of Michael Davitt, according to the author? It appears that despite bad treatment he appears to have been almost a model prisoner. Reading the extensive, surviving official records, public accounts and private papers dealing with Davitt’s imprisonment (there are three in all) he emerges as a person of integrity, one who would not willfully misrepresent his experiences.

In the bibliography of prison writings, this is a rare quality and, being thus perceived by his contemporaries, it enhanced his moral and political stature, giving weight to his writings on prison matters.

We are told that he was “no turbulent Rossa” and his prison record shows only a handful of disciplinary reports, and those of the most trivial kind. McConville concludes that Davitt was a man who tried to survive in the convict system, keeping his mental and emotional balance, and limiting the damage which could undoubtedly arise from a long confinement.

The author’s view and opinions on Roger Casement may provoke controversy particularly on the subject of the ‘Black Diaries’. His lewd description of Casement’s alleged sexual exploits left me wondering why he had to go into such detail. Controversially, he states, and I quote, “Although arguments raged for many years after Casement’s death, there can now be no doubt that the diaries and ledgers are genuine”. The references, of course, that he used to ‘confirm’ such claims were the work of the secret services in Britain. Enough said.

There is extensive coverage of the hunger striker Terence McSweeney, Lord Mayor of Cork. As he lay dying, we learn of the skullduggery that went on between the prison authorities and medical officials – and the medical help, or lack of it, that McSweeney received. The question of force feeding is reminiscent of the treatment meted out to Thomas Ashe and four of the ‘Belfast Ten’, including Gerry Kelly, Hugh Feeney and the Price sisters.

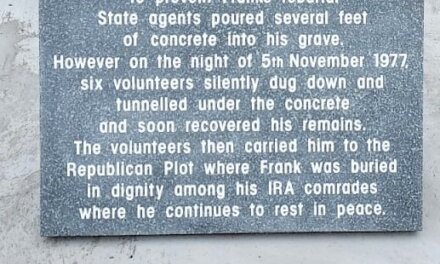

A debate takes place over the state’s refusal to hand McSweeney’s body over to his relatives. I found this most interesting and ironical, considering that the foreword to the book is by former Taoiseach, Garret Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald was a minister in the Fine Gael/Labour coalition government which in 1976 hijacked the remains of IRA hunger striker Frank Stagg, to prevent his family and his comrades giving him a republican funeral. Did Fitzgerald even blush as he wrote the foreword?

The last three sections deal with the handover of British power and the period up until 1922. Much of the detail will not be new to avid historians. However, as this book is about prisoners, it is significant that the author recalls the final campaign for the release of those caught on the northern side after the Treaty. After the signing of the Treaty, the Free State Government sought their release as part of a policy to ‘close the books’ and because clemency would be politically advantageous.

Two men in particular are named: John McCurtain, whose brother had been a commandant in the Free State Army killed by republicans in Tipperary, and John Flood , whose brother was shot dead by the British in March 1921. The British government, in the years immediately following, undertook to act as intermediaries with the North’s government to review the cases of prisoners who had been sentenced because of their part in the ‘invasion’. The North’s Prime Minister, James Craig, agreed to allow the British government to review these cases, and to accept the resultant recommendations. Thirty-three men were released on January 25, 1926.

With these releases Britain ended the part it had played in that Anglo-Irish war and its immediate aftermath. Though not of course, its involvement in Ireland and confrontation with Irish revolutionary politics.

New ‘cohorts’ had entered the system, and would have a presence there for most of the Twentieth Century.

For historians this book is a worthwhile and powerful work of diligent research. I recommend it with the proviso of a health warning for republicans who would perhaps argue with some of the polemic that underlines some of its assumptions.

Irish Political Prisoners, 1848-1922, published by Routledge Taylor and Francis

London and New York