Former hunger striker Laurence McKeown’s interview with Anns Sussman on NPR (formerly National Public Radio). NPR serves as a national syndicator to a network of 900 public radio stations in the United States. This is the text of the interview which can also be heard and viewed here.

You’re listening to SNAP JUDGMENT, the “To The Brink” episode. Today, we’re speaking with people forced past their personal breaking points. And our next story, it’s about commitment like you’ve never heard before. And it comes to us from SNAP JUDGMENT’s Anna Sussman.

ANNA SUSSMAN, BYLINE: A young prisoner in Northern Ireland approached a fellow prisoner after mass one Sunday and volunteered for a mission which would guarantee his death within a hundred days.

LAURENCE MCKEOWN: I was 24 years of age. I was single. I put my name forward. After that, there would be people joining it when someone died.

SUSSMAN: Laurence volunteered to join a hunger strike. It was a part of a series of very dramatic protests by Irish Republican Army fighters in prison.

MCKEOWN: I was told after four had died that I was going to be the next one to join it on the 29 of June. I then got a very short communication from the IRA’s Army Council, just written on a – on one cigarette paper, which said, comrade, you have put forward your name for the hunger strike. You realize, of course, that this means that you will most likely be dead within the next three months. Re-think your decision – Army Council. So it was very stark – if you had any second thoughts about not going through with it, but I didn’t have. And I don’t think anybody made the decision lightly. The fact that four people had already died didn’t change my opinion on it.

SUSSMAN: Laurence is Catholic. He grew up watching as his family lost more and more of their rights in Northern Ireland. They were treated with increasing hostility by the government and then by their Protestant friends and neighbors.

MCKEOWN: I think it’s tragic that I was born into a society where Catholics were discriminated against in the way they were. My parents’ generation kept their heads down. I think that my generation weren’t prepared keep their head down. They didn’t raise up in armed struggle. They rose up in peaceful protest on the streets. And then they were shot off the streets. And I’m proud that just my generation then said, well, we weren’t just going to be carried. We weren’t going to be broken.

SUSSMAN: Laurence made the choice to take up arms, to join the IRA. He was convicted of causing explosions and attacking a police officer. And when he landed in prison, the British government had just revoked the status of political prisoner it had been giving to IRA inmates.

MCKEOWN: Well, the British are saying we were criminals, we were saying that we were political prisoners and that the struggle on the outside is a political struggle. Then, we seen the need to take us down. And that the idea that we would wear prison clothes, do prison uniform and meekly say that we were criminals was just not something that was going to happen as far as we were concerned. It wasn’t done lightly. It wasn’t done fatalistically. It was done because we believed that this was something we needed to do.

SUSSMAN: The first striker, Bobby Sands, died after 66 days. And Laurence says when the news of his death spread, the prison went quiet.

MCKEOWN: It was early in the morning after the prison guards come on. And it’s a very strange feeling. The wing was very, very quiet. There was no shouting or anything else.

SUSSMAN: Then Francis Hughes, the second hunger striker, died. The third died quickly after him. A fourth man died after 61 days. Then it was Lawrence’s turn to join the strike. He wanted to tell his mother before she heard it on the news.

MCKEOWN: The most difficult thing was to say to families that you were going to join a hunger strike and particularly at that stage after four people had died. I was very close – all through my life, I was very close with my mother. I think when I first told her I was going on a hunger strike, more or less, she was resigned to it. Obviously, she was in turmoil at the same time. That was the strongest thing about her. She would never have used her love for me in a way that was – well, you better do this if you love me. Or – I started with the hope that I would live, that something would happen. In terms of fears, there was always the concern – I think everybody, when they’re putting their name down thought, what will it be like at the end? Will I have the ability to go through with this? Will I have the commitment to see this through to the end?

SUSSMAN: The first day, the guards brought Laurence his breakfast, and he left it untouched. They brought him a tray of lunch and then a tray of dinner.

MCKEOWN: It became more of a torture rather than anything else. I was – in terms of just the smell of it. For the first three days, I think you still feel hungry. But I think after that – it’s hard to describe it. So some of my initial memories was feeling cold, so many aches and pains. And it was very strange as time went on. I just couldn’t – I couldn’t listen to music at all. And the only music that I could end up listening to was the music that I previously detested, which was country-western music or particularly the Irish version of country-western music.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MCKEOWN: I think it’s because the music itself is so thoughtless, you don’t have to actually think about it or the lyrics are so stupid you don’t have to – apologies to any, you know, country-western fans.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

SUSSMAN: Eventually he became so weak, he was moved to the prison hospital with the other hunger strikers.

MCKEOWN: You become aware of just how weak your body is. You start – obviously you see yourself in the mirror, and you’re basically skin and bones. You’ve got to remember is by that stage, you’re totally exhausted. So it’s not like you’re sitting a day and thinking, I’m going to die now. Later on in the day or in a couple of days’ time, how do I feel? It’s not like that at all. You sort of fall in and out of consciousness. You try to use every ounce of your energy to stay alive and keep going.

SUSSMAN: He only drank salt water – about 10 pints a day. Weeks passed and then he began to lose basic functions.

MCKEOWN: After about 40 days, eyesight starts to go – seeing double vision but very clear double vision. And then after probably about 50 days, double vision went and it became just like a blurred vision.

The other thing I should say went – the sense of smell really dramatically increased, so, like, the smell of food. And the prison authorities would put the food into our cell. Every day, they’d put on breakfast. They would take the breakfast out at lunchtime and put on a lunch. They’d take a lunch out in the evening and put on a supper. So actually as the food sat there and got cold and congealed, like, the smell of it was sometimes overpowering.

One of the smells at one time I was very curious about and sort of looked about the cell to see what was going on. And what I realized, that odor was the smell of my own body where it’s disintegrating. Your body is starting to smell like rotten flesh, which was a sort of a stark discovery.

SUSSMAN: Since the day he walked into Long Kesh Prison, Laurence’s mother made regular visits to see him. And she kept up her visits once he was moved to the prison hospital. As his body thinned out, the reality of his commitment to the strike dawned on her. Laurence said he could see the pain she was causing her. It was written all over her face.

MCKEOWN: Visits on the hunger strike were very awkward. And all the decisions I had taken was causing my family real grief. And basically it was, on those visits, it’s more about what’s not said rather than what is said. And we ended up talking about everything other than what’s actually happening right in front of you because, in some sense, there’s – you know, a conversation’s not going to go anywhere. I am on hunger strike. I was again repeating that I was stand – on hunger strike and that was my wish.

SUSSMAN: Then Laurence’s father, who had never visited him before, came to see him in the prison hospital.

MCKEOWN: I just love my father. He was shuttered in many ways. My father always wore a cap, but he had the cap off, and he kept squeezing it his hands turning it around his hands. And then finally he burst out about coming off the hunger strike, and did I know the impact it was having on my mother? And I said I did and – but I said I wasn’t – I wasn’t coming off it. That’s the tragic thing about it, too, he – just looking at him and – he’s totally powerless. He doesn’t know what to do or what to say or – it’s like the applecart turned upside down. The sons and daughters are overtaking the parents, even at a very young age, sort of the parents feel powerless.

SUSSMAN: Laurence reached 60 days with no food and then 65. No hunger striker had lived more than 66 days.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MCKEOWN: I’d always had fantasies that, you know, the door is going to suddenly open and somebody’s going to say, oh, yes, it’s over or – that’s the sort of thing you live with, the hope and, you know, visualize how this is going to happen and what you’re going to do once it happened and what you were going to eat.

SUSSMAN: At one point, Laurence was called from his cell. He was told there was to be a meeting with three Sinn Fein leaders.

MCKEOWN: They said look, if you sort of call off your hunger strike now, the Irish people will have nothing but admiration for you. If you stay on your hunger strike, what you can be sure of is everybody around this table will be dead within the next few weeks. But our response was, well, we’re not – we’re not stopping it.

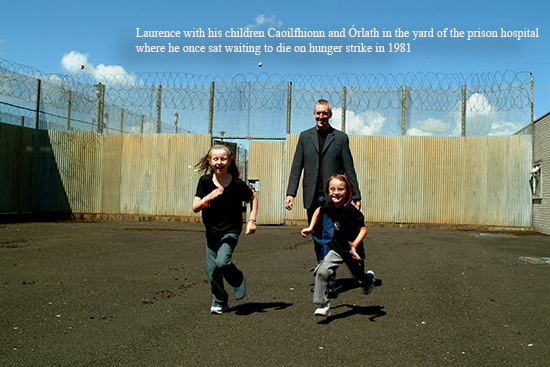

SUSSMAN: Laurence and the remaining hunger strikers – those who weren’t bedridden – spent their time on plastic chairs in the hospital yard, staring into space, making occasional small talk, waiting to die.

MCKEOWN: And we were sitting in the yard, a number of us on the hunger strike and started to hear these real strange sounds coming from one of the cells. I’ve tried to describe it, and it sounded to me like in an animal, like a cow or something who had been in distress. I had grown up in the countryside, and I knew that it was one of the guys on hunger strike, Paddy Quinn. And he was doing this real deep roaring and then it would change into a very high-pitched – almost like a giggle, somebody giggling – but then you hear this – they started laughing and then there would be maybe a period of silence and then this really deep, deep sobbing, heart-wrenching sobbing.

I was in a cell just two doors down from Paddy. And the other sound that I could hear was his mother. She was sitting with him. And I could hear her just – just speaking to him very gently, which was a real juxtaposition of Paddy, I’d say, screaming, bawling, sobbing and then his mother just saying, you’re all right, Paddy, stay calm, just generally trying to comfort him.

SUSSMAN: And then came a moment, a decision that changed the fate of the hunger strike and almost every man on it. Paddy Quinn slipped into a coma, and his mother was given power of attorney. She had him moved to a hospital and put on an IV drip.

MCKEOWN: Well, he would have died within a few hours if his mother hadn’t have authorized medical intervention. I think there’s a part of me that said I’m glad that you did because I knew Paddy well. It’s obvious this person was in extreme agony. The other part of me was now what will happen? I mean, this is going to impact on our whole strategy here.

SUSSMAN: The iron will of the protesters had met its match – not in the unforgiving prison system or in Margaret Thatcher, but in the force that erupted from the breaking hearts of their mothers and fathers.

MCKEOWN: We had a closeness with our families. We could understand the tragic nature of it, that they’re watching people die one after another. So there’s a mixture of emotions. There’s a realization that this is – very potentially could undermine the hunger strike.

SUSSMAN: When Laurence reached his 68th day on hunger strike, his family was called in to be by his side.

MCKEOWN: I remember them coming in, being at the bottom of the bed and my mother sitting at the side of it and sister crying. And my father and my brother and sister had again asked me to come off it. I said I wasn’t coming off the hunger strike. And I sat there with my mother, and I know she was holding my hand. But what I do remember is her saying, you know what you have to do and I know what I have to do.

SUSSMAN: When Laurence slipped into a coma, his mom had him hospitalized and brought back to life. Days later, in the ICU of the Royal Victoria Hospital, he heard a woman’s voice – a nurse.

MCKEOWN: That moment I realized that I was alive; was neither happy to be alive or sad to be alive, I just knew I was alive. I knew what must have happened and allowed me to be there in the intensive care unit. And I had no real sensation of what that meant or how I felt about it.

SUSSMAN: He was transported back to the prison, where some of his comrades were still on hunger strike.

MCKEOWN: And that was a very stark situation because I was still very unstable. I was still very – I could hardly see. I had been walking with the aid of prison guards. We were just passing individual cells where some people were still on hunger strike, and I can hear the noises that you would associate with hunger strike, which is like maybe throwing up water or just sounds of illness. And I knew them – some of them were close friends.

Comments from some of the prison guards was, here’s another failed hunger striker. I didn’t go back on the hunger strike because I just didn’t have the willpower to do that. Anyone who was taken off the hunger strike by their family, none of them went back on it again.

By that stage, there was a realization that the hunger strike would have to be called off. And that caused a lot of soul-searching. You’re caught between family and comrades; that’s basically down to it. We had a job to do in the jail. We had a job to do as being volunteers in the IRA. But at the same time, we had families who loved us and who we loved. So I think what we did what – we believe we should do – I did what I believed that I should do that day.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

WASHINGTON: Laurence McKeown went on to write some fantastic plays about the hunger strike. You can find out more at our website, snapjudgment.org.