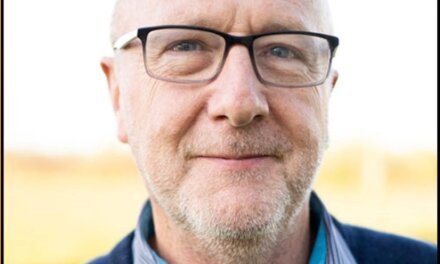

In 1981 Jim Gibney, a member of Sinn Féin and of the National H-Block/Armagh Committee, liaised with the hunger strikers in the H-Block prison hospital. He tells of that period in the book, The Comrades

Three months after the hunger strike ended Jim was arrested, whilst visiting the prison, and was sentenced to twelve years in one of the notorious supergrass trials of the early 1980s. His conviction, which still stands, has long been discredited. He now works as an assistant to Senator Niall Ó Donnghaile in the Irish Seanad.

BOOK REVIEW

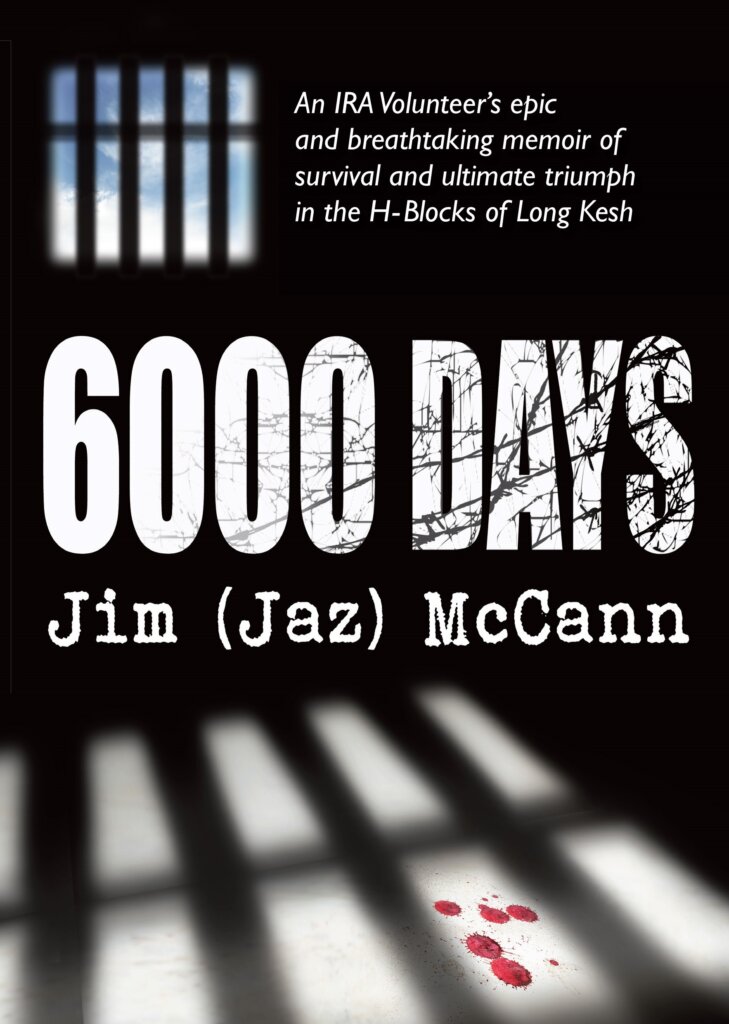

6000 Days by Jim (Jaz) McCann, published by Elsinor, 2021

By Jim Gibney

At a Féile an Phobail event in West Belfast a number of years ago the historian, author, journalist and literary critic Ulick O’Connor said of the protesting prisoners in the H-Blocks and Armagh Women’s Prison, that never in the annals of world or Irish history had a group of prisoners displayed such heroism, bravery and loyalty to each other and to the cause of Ireland.

Over the years I thought about his remark often; about its accuracy, about the women and men he was describing in such apt and admirable terms.

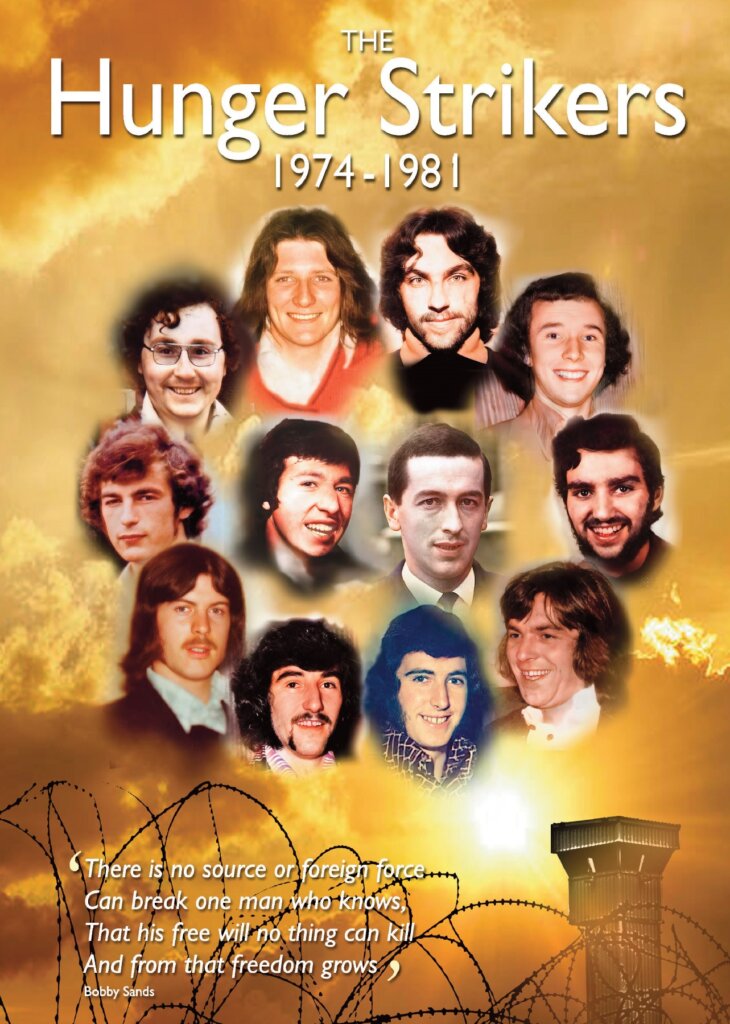

But more particular I was looking for an opportunity to highlight Ulick’s comment in a public expression of what took place in the prisons between September 1976, when Kieran Nugent refused to wear a prison uniform and donned a prison blanket, with such nobility, and became the first ‘blanket man’; through a harrowing and brutal, five-year-long protest, involving hundreds of political prisoners, which resulted, in the deaths of ten hunger strikers.

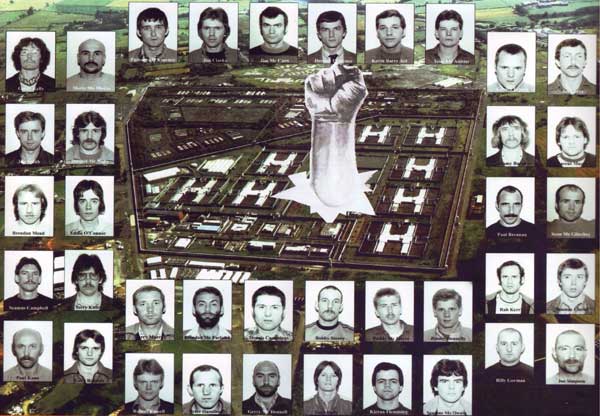

Ulick’s remarks, commentary, become real with, now, the testimony in Jim ‘Jaz’ McCann’s epic, 6000 Days—a tour de force of personal resistance, amidst the incredible protest for political status in Armagh Jail and in the H-Blocks which at its height involved almost five hundred prisoners.

6000 Days records, in the finest of detail, the ‘hell-hole’ that the H-Blocks were and the herculean struggle of the prisoners and their daily deprivations and sufferings in the H-Blocks to uphold the dignity of the freedom struggle and the legitimacy of armed struggle as politically motivated and a reaction to British rule.

The resistance was a joint endeavour between the political prisoners in both the H-Blocks and Armagh Women’s Prison; an endeavour which stretched them, body and mind, and had them walk a very thin line between sanity and insanity as the prison authorities unleashed extremely personal violence.

But 6000 Days is much more than a prison memoir. It is a memoir of a generation of IRA volunteers who fought the British Crown forces on the battlefield which was the north and carried on that battle, ‘on active service’ in the cells of the H-Blocks and Armagh.

It is a memoir which brings you inside the mind of young IRA Volunteer Jim McCann, whose actions and conviction, reflect that ‘sinew of war’ quality that the IRA displayed outside and inside the prison.

It is an invaluable insight into the qualities which made the modern IRA the force it was, with the capacity it used against the British because, put simply, the IRA, in the sum of all its parts, integrally involves Jim McCann and his comrades who in the darkest of dungeons drew on their inner selves, that desire for freedom, that ‘thought that says “I’m right”’, as Bobby Sands put it in The Rhythm of Time.

These volunteers, in their hundreds, average age nineteen, were not only prepared to engage in war with the British on the streets risking their own lives and liberty, but within prison to protect the integrity of a struggle which Thatcher claimed was ‘criminal’ and the hunger strike as ‘the IRA’s last card’.

The protest for political status was a prisoner-led response to the attempts by the British government to criminalise the freedom struggle.

On practically every page of this book—some 260—you will read about experiences over seventeen years that will leave you in awe.

Jim’s friendship and comradeship with Joe McDonnell was special. Jim’s admiration for Joe encapsulates the unbreakable bond between the prisoners—a bond which sustained Joe and his comrades through to their deaths.

In the service of Ireland and freedom they endured beatings and deprivations. Joe was a great source of strength through the force of his personality which consisted of a no-nonsense, tough resolve, with an acerbic sense of humour and thoughtfulness and love, especially for his wife Goretti and children, Bernadette and Joseph.

In the midst of the bleak prison conditions the affection between Jim and Joe is a reminder of the human spirit’s ability to thrive and retain its essential goodness in the face of unrelenting brutality.

A reminder too that when we are literally stripped of all our worldly possessions, it is the convictions forged by community and history which prevail and guide us.

The book is written in a style which has you there: in the maggot-infested cells covered in excrement; while the prisoners are being starved; beaten on wing shifts; beaten during the depraved mirror searches; beaten in the cell; beaten as their heads and beards are forcibly shaved; beaten as they were forcibly bathed and scrubbed with yard brushes, bodies left bleeding and raw; hosed down with high-powered hoses similar to those used by the fire-service; overcome with toxic fumes; deprived of sleep; bodies wracked by penetrating, biting, pervasive wintry weather, and not only denied medical attention by doctors and prison medics but wilfully denied it in full breach of their Hippocratic Oath. Regular punishments of three days’ bread and water for disobeying rules—declared illegal by the European Court of Human Rights.

Little wonder Cardinal Tomas Ó Fiaich said after visiting the H-Blocks, three years before the hunger strike, ‘One would hardly allow an animal to remain in such conditions let alone a human being. The nearest approach to it I have seen was the spectacle of hundreds of homeless people living in sewer pipes in the slums of Calcutta.’

6000 Days is a gruelling story, of naked and vulnerable young men going ‘toe-to-toe’, ‘eye-ball-to-eye-ball’, ‘limb-to-limb’, ‘mind-to-mind’, ‘hour-to-hour’ for nearly five years, with their vengeful and insatiable tormentors, fired up by Thatcher’s bombastic rhetoric that she and they could beat the IRA.

To prove her so wrong a terrible price was paid by the prisoners. Outside the prison almost seventy died in related violence including children killed by plastic bullets, thirty thousand of which were fired by the British Army and the RUC in 1981. Thirty thousand. Prison warders also died, though none had been attacked by the IRA until the introduction of criminalisation in 1976.

Throughout the prison protest the people of Ireland, north and south, marched, firstly in street demonstrations organised by Relatives Action Committees, and then in their tens of thousands, under the National H-Block/Armagh Committee, culminating in the massive show of support in elections for Bobby Sands, Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew. The people of Fermanagh and South Tyrone were subjected to unprecedented warnings and vitriol should they elect Bobby Sands. Not only did they elect Bobby, but after Thatcher amended the electoral law barring prisoner candidates, they went on to elect as the MP Bobby’s election agent, Owen Carron. To this day, in what is a great example of British spite, Owen is still barred from entering the North.

While the prisoners died on hunger strike and women and children were killed on the streets, H-Block/Armagh campaigners also died at the hands of loyalist assassins acting in the British government’s interest: Miriam Daly, John Turnley, Ronnie Bunting and Noel Little. Bernadette McAliskey and her husband Michael, despite suffering multiple gunshots, were lucky to survive.

In the United States Irish supporters mobilised like never before in a desperate attempt to save the lives of the hunger strikers. The leading Democratic Party representative, Richie Neal, became interested in Ireland through the hunger strike and remains so to this day.

The late Cuban leader Fidel Castro spoke in the United Nations in support of the prisoners.

Nelson Mandela was inspired by the hunger strikers.

At home a new generation, outraged at Thatcher’s arrogance, joined and strengthened the Republican Movement.

It is entirely fitting that Jim’s heroic, riveting, angry, honest, inspirational and at times brutal book, should open with an account of the greatest prison escape in the IRA’s history from which (the British boasted) was the highest security prison in Western Europe—the H-Blocks of Long Kesh.

Fitting because the great escape is the IRA at its best, with all its skill being employed, inside and outside the prison, to carry off the most daring and spectacular prison escape.

An escape carried out by a group of IRA volunteers who had endured, with their comrades in Armagh Women’s Prison, a daily diet of brutality and inhumanity at the hands of sectarian, bigoted warders, which lasted for five years and ended with seven IRA and three INLA volunteers, dying on hunger strike in the summer of 1981.

From its inception to its execution the escape plan needed nerves of steel and determination by those involved—a self-belief and an unflinching conviction—where life and limb are employed, to effect an outcome.

In this case freedom for the thirty-seven prisoners hidden in the back of a food lorry being driven through the prison complex, breaching security posts at ‘the various phases as we silently exited Long Kesh’, as Jim describes it in the introduction.

The prisoners on the food lorry and their comrades in a back-up role, had audaciously ‘secured H7, taken over the entire block, arrested the prison officers and stripped them of their uniforms, which some of us now wore.’

Gerry Kelly was the ‘armed navigator’, hidden in the well of the front passenger seat, pointing his gun at the prison guard driving the food lorry to the front gate and freedom.

In the preparation for the escape, ‘There was no talk of Plan B. Plan A was going to work. Sin é,’ writes Jim.

In the circumstances this black and white attitude drove the prisoners and fuelled what on paper was an escape plan layered with so many fatal pitfalls as to make it a pipedream.

In the realm of possibilities, the escape plan should never have made it out of the heads of its ingenious schemers never mind been a major success, albeit with some immediate and some subsequent arrest and captures, including some extradited by the Irish government and handed over to the British. Three of the IRA escapees, Kieran Fleming, Séamus McIlwaine and Pádraig McKearney would die on active service.

The escape, masterminded by Larry Marley (assassinated by British agents) and led by the late Bobby Storey, occurring just two years after the hunger strike was a victory of seismic proportions for the IRA outside the prison. Inside, it ironically led to the completion of the restoration of political status, and recognition of IRA command structures, until the early release of the prisoners under the Belfast Good Friday Agreement.

On the first day of his hunger strike on 1 March, 1981, Bobby Sands wrote, ‘I am dying not just to attempt to end the barbarity of H-Block, or to gain the rightful recognition of a political prisoner, but primarily because what is lost in here is lost for the Republic and those wretched oppressed whom I am deeply proud to know as the “risen people”.’

Jim McCann’s book records graphically the loss for the prisoners, their families and their community.

And history records the ‘gains for the Republic’ brought about by the prisoners’ defence of the freedom struggle, most noticeably the electoral growth of Sinn Féin and the popularity of Irish republicanism

Without the protests in the H-Blocks and Armagh it is hard to imagine where we would be today. The prisoners and the people defeated Thatcher’s attempt to criminalise one of the oldest struggles for national independence.

Their stance fundamentally changed the struggle from it being an armed struggle only to being a broader one with Sinn Féin emerging as a formidable radical republican party, which began in Bobby Sands’ prison hospital cell when he agreed to stand as a candidate in the by-election in Fermanagh and South Tyrone.

A heroic chapter – among many heroic chapters in Ireland’s long struggle for freedom.

6000 Days, an epic tale of endurance, is timely on this the fortieth anniversary of the hunger strike.

We stand in awe.

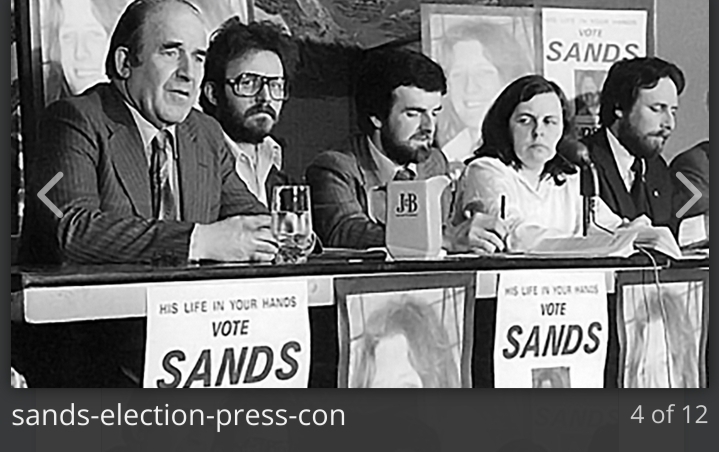

Jim Gibney (2nd from left) in 1981 at election press conference. Neil Blaney TD (left); Owen Carron (middle); Bernadette McAliskey; and Independent Councillor Pat McCaffrey