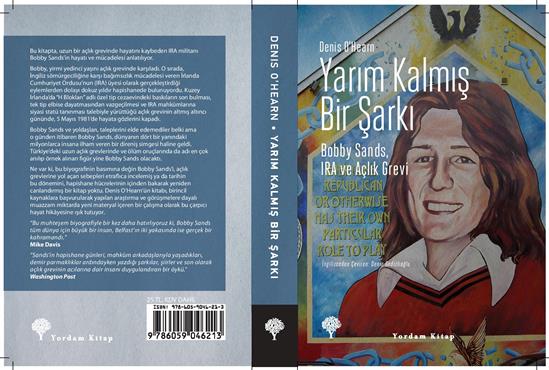

Next week sees the publication in Turkish of Denis O’Hearn’s biography of Bobby Sands, Nothing But An Unfinished Song. The book will be published in time for the Istanbul Book Fair, November 8th -11th . The book, under the Turkish title, Yarim Kalmış Bir Şarkı: Bobby Sands’in Hayatı ve Dönemi, is published by Yordam Kitap of Istanbul.

Next week sees the publication in Turkish of Denis O’Hearn’s biography of Bobby Sands, Nothing But An Unfinished Song. The book will be published in time for the Istanbul Book Fair, November 8th -11th . The book, under the Turkish title, Yarim Kalmış Bir Şarkı: Bobby Sands’in Hayatı ve Dönemi, is published by Yordam Kitap of Istanbul.

The publication of the biography of Bobby Sands in Turkish is especially poignant because more than 100 political prisoners and their supporters died on hunger strike in Turkey during 2000-2007, an action which they claimed was in the tradition of Bobby Sands and his comrades. In 2012, Kurdish political prisoners went on hunger strike for 68 days, again citing the influence of the Irish hunger strikers of 1981. Students were arrested when they followed an Irish tactic of the H-Block protests, writing, “Kurdish prisoners are on hunger strike in F-type Prisons” on Turkish banknotes.

The original title of the book, Nothing But an Unfinished Song (Yarım Kalmış Bir Şarkı) comes from a poem written in Bursa prison in the 1930s by Turkey’s greatest poet, Nazim Hikmet.

In his preface to the Turkish edition, Denis O’Hearn writes:

It is especially moving to me for this book to be published in Turkish. The title, of course, is taken from a poem that was written by Nazim Hikmet while he was in Bursa prison. The degree to which Hikmet’s image of the “unfinished song” fits the life of Bobby Sands is uncanny. Not only was Bobby’s life filled with music – songs of other people that he sang and songs that he wrote himself – but his life itself was and is a wonderful song. It was often sung in the most horrible places and circumstances, and his physical song was left unfinished when he and nine other courageous young men died on hunger strike in 1981. The H-Blocks of Long Kesh prison outside of Belfast, where Sands and hundreds of men suffered and died for their ideals, was the site of one of the most horrible episodes in prison history. For five years hundreds of men were kept naked in their cells, with only blankets to wear. They were beaten and abused. They were the “blanketmen.” Yet through all of the horrors of that period, which you will read about in this book, Bobby Sands sang his song, with great power and joy. And although it remains unfinished, it lives on through other free men and women across the world and new verses continue to be written.

This is another reason why this book should be available in Turkish, and hopefully one day will be read in Kurdish. The English-language version of this book was published in 2006, at the end of a horrible death fast in Turkey, a fast that was undertaken by prisoners and their supporters who said they were acting in the tradition of Bobby Sands and his comrades.

In the intervening years this book has been into many dark places like those endured by the Irish prisoners in the H-Blocks and the Turkish death fasters.

“Supermax” prisons in the United States are dark places where tens of thousands of men spend years and even decades locked into small cells the size of a parking space, never touching another living thing, human, animal, or plant. Some have been there for decades, watching their loved ones grow older in rare visits, never touching, having to shout their love to one another through panes of security-glass or over a telephone headset. Like Bobby Sands, these men struggle in ingenious ways to practice mutual aid and solidarity, to make contact with each other through word and deed, even though they cannot make physical contact. They find ways to communicate. They share knowledge. Like Bobby and his comrades, they find ways to open the “windows of their minds,” even as their torturers close off the windows to nature and life that nourish all of our spirits in more normal places.

After this book was published, things began to change. A light began to glimmer in the darkness. The book never made the best seller lists, nor has it made its author a rich man in monetary terms. But it has provided much greater riches. Soon after this book was published it made its way into the hands of an African-American man who had been in a supermax prison in the American state of Ohio living in the conditions I have described above for fifteen years. That man, Bomani Shakur, wrote a letter to me and we have since become the closest of friends; no, we are brothers. Bomani found in this book a spirit that helped him and his comrades, sentenced to death for their alleged part in a prison uprising in 1993, to begin thinking about how another world was possible, even in the horrible conditions of solitary isolation.

I began visiting Bomani at Ohio State Penitentiary, a six hour drive away from my home in New York. We talked about many things, but mostly about the meaning of freedom. In 2009 he suggested to me that I should teach a course on prisons at my university, and that supermax prisoners could also participate, both as students and expert consultants. The class included students from assorted ethnic and class backgrounds, and ten prisoners held in long-term isolation in supermax prisons across the United States. They included Bomani Shakur but also two remarkable men from the most infamous prison in America: Pelican Bay State Prison in California. In fact, Danny Troxell and Todd Ashker were not just from the “Secure Housing Unit” (SHU) at Pelican Bay, they were from a small part of the SHU called the “short corridor,” where the state of California keeps two hundred prisoners it wants most to silence. They are men of different races: whites, African Americans, and Latinos. According to the state of California, these men are supposed to hate each other. But, instead, they formed a “short corridor collective,” where they built a community by shouting to each other from cell to cell. They shared ideas of freedom from writers like Thomas Paine and the radical historian Howard Zinn…and Bobby Sands.

According to Todd Ashker, “we’ve come to recognize and respect our racial and cultural differences…while recognizing that we’re all in the same boat when it comes to the prison staff’s dehumanizing treatment and abuse – they are our jailers, our torturers, our common adversaries.”

In 2009, these men participated in my course on “prison experiences.” They read the same books and articles as the students. Then the students wrote to them, asking questions about how life really is in prison. They asked whether famous academic prison experts, like the French social theorist and philosopher Michel Foucault, “got it right” (a short answer: no, they usually didn’t get it right).

The prisoners all read this book in the class, which you can now read in Turkish. The experiences of Bobby Sands and his comrades, though they happened thirty years previously, spoke to them across the years. They studied the Irish experience and they thought about how they, too, could fight the supermax and its tortures through non-violent actions including hunger strike.

In 2010 thousands of prisoners in the state of Georgia went on a general strike, refusing to obey the orders of the prison authorities or to do prison work (if, indeed, they were allowed to work). In early 2011, Bomani Shakur, Jason Robb (a white man), and Siddique Abdullah Hasan (a Sunni Muslim) went on hunger strike. Like Bobby Sands and his comrades they had five demands. At the top of the list was to have open visits with their friends and family and to be able to exercise together. Also like Bobby and the “blanketmen”, they reached out to supporters outside of prison and built a network of people who could undertake actions in their support: attending public demonstrations, writing editorials in newspapers outlining their case.

After twelve days without food, the men won all of their demands. A week later, I went to visit them along with my Turkish wife, Bilge. We hugged, kissed and broke bread together, the first time these men had been allowed human contact in almost twenty years. Bomani Shakur and Jason Robb (who are, incidentally, best friends even though the prison authorities insists they should be enemies because they are from different races) have both told me that Bobby Sands gave them their freedom. He and his Irish comrades showed them the way, gave them a vision of how they could win their rights. And they struggle on, but now living a life that is richer because they discovered how they could fight for their rights.

Meanwhile, our friends back in Pelican Bay also read about Bobby Sands and they heard about prisoners winning their rights in Georgia and Ohio. In the “short corridor collective,” men of mixed races who are supposed to hate each other discussed freedom. From their readings of Mayan cosmology (the Mayans are an indigenous people in Mexico and Central America) they learned about time and space, and how to identify opportunities to move to a better and higher way of living. The talk across the corridor was often loud and confused; some spoke in Spanish and some in English. But Todd Ashker says, “when Danny and I started talking about Bobby Sands and the Irish struggle, things went quiet…everyone was listening.”

The men of the short corridor slowly began to make plans for a hunger strike against California’s system of prison torture. Slowly, they got the word of their plans to prisoners all across the state of California. In 2011 and again in 2013, more than 30,000 prisoners in California went on hunger strike. Again, like the Irish, they had five simple demands. First among them was to end the system of isolation, where a man could only get back among other humans if he snitched on other men.

They launched a legal campaign against the prison system and forced the California legislature to hold hearings about the conditions at Pelican Bay and other prisons in California. The struggle continues.

In the state of Illinois, more prisoners took the class on Prison Experiences in 2014. They all read this book. Later that year they launched their own hunger strike against the prison system in that state. One of them wrote to me saying that, like the Northern Irish prison authorities, the Illinois authorities were putting metal over their windows, shutting out their only contact with nature. But he said that the men were standing firm. They would not be deterred from their fight for freedom. The spirit of Bobby Sands and the “blanketmen” of Long Kesh prison continues to speak to prisoners, across continents and across millennia.

A French edition of this book came out in 2011. It found a special audience and had special meaning to Basque prisoners in the southern parts of France, also known as the Basque Country. After some months, two prisoners from that region wrote to say that they were translating this book into Basque so that their own people in struggle can find encouragement from Irish comrades of times past.

In 2012, we shared the Prison Experience course with a remarkable group of students at Bogazici University in Istanbul. Also participating in the course were many leftist and Kurdish men and women prisoners, most of them enduring that other infamous system of prison torture and isolation: the F-type prisons. We stayed as close as we could to the same pattern of learning and sharing that we had developed in the United States with prisoners in the supermaxes. In Turkey, we found the same spirit of freedom that we found in the United States. We shared some of the life and work of Bobby Sands with prisoners in F-type, although we were hampered by problems of translation. We sent this book to a few Kurdish prisoners who spoke English.

Now, in this translation, all free men and women in this territory—captives and noncaptives; Turkish and Kurdish and Roma and Armenian; Sunni and Alevi and Christian and atheist—can share in the life of Bobby Sands and his remarkable comrades. Many already know and practice the same ideals of freedom that Bobby practiced. I know that it will enrich you to read of Bobby’s experiences, as it has enriched people all across the Americas, Europe, and Australia. Most of all, I hope that those of you who read this book will send copies into the prisons of Turkey. The captives in Turkey are Bobby’s people. They will understand.